Explore Business Standard

Explore Business Standard

Associate Sponsors

Co-sponsor

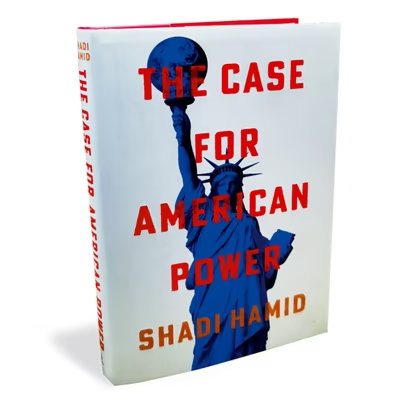

Shadi Hamid's argument for a world with the US as the sole hegemon is more confused than convincing

)

The Case for American Power By Shadi Hamid published by Simon & Schuster

Premium ContentPremium ContentSubscription ExpiredSubscription Expired

Premium ContentPremium ContentSubscription ExpiredSubscription ExpiredIntroducing Blueprint - A magazine on defence & geopolitics

From military strategy to global diplomacy, Blueprint offers sharp, in-depth reportage on the world’s most consequential issues.

annual (digital-only)

₹208/Month

annual (digital & print)

₹291/Month

annual (digital-only)

₹291/Month

annual (digital & print)

₹375/Month

Access to the latest issue of the Blueprint digital magazine

Online access to all the upcoming digital magazines along with past digital archives

Delivery of all the upcoming print magazines at your home or office

Full access to Blueprint articles online

Business Standard digital subscription

1-year unlimited complimentary digital access to The New York Times (News, Games, Cooking, Audio, Wirecutter, The Athletic)

Access to the latest issue of the Blueprint digital magazine

Online access to all the upcoming digital magazines along with past digital archives

* Delivery of all the upcoming print magazines at your home or office

Full access to Blueprint articles online

Business Standard digital subscription

1-year unlimited complimentary digital access to The New York Times (News, Games, Cooking, Audio, Wirecutter, The Athletic)

In this article : BOOK REVIEW

Next Story