A little over 40 years ago, when I joined the Planning Commission, Professor Sukhamoy Chakravarthi asked me to conceptualise a model for short-term macro-policy analysis. My response was in the genre of a monsoon compensation model with two sectors — agriculture and non-agricultural.

Agriculture, in the short run, was modelled as fixed quantity and flexible price sector, the fixed quantity depending on the monsoon and agricultural prices being determined by domestic demand and supply. Non-agriculture in the short run, on the other hand, was modelled as fixed price and flexible quantity sector, output and capacity utilisation being determined by effective demand given the impact of the monsoon determined agricultural growth.

A small departure from the fixed price formulation of the non-agricultural sector came through the modelling of the impact of agricultural prices on budgetary resources and on non-agricultural prices via wages and raw material costs. The impact of international terms of trade was also considered as part of cost push inflation. But given the lower ratio of international trade to GDP, this was not of great consequence, except when abnormal price shocks occurred.

This monsoon compensation model was never estimated but the conceptual structure does give an indication of the drivers of macroeconomic policy then. The challenge of short-term macro-economic management is now radically different and must take into account the following key difference between then and now:

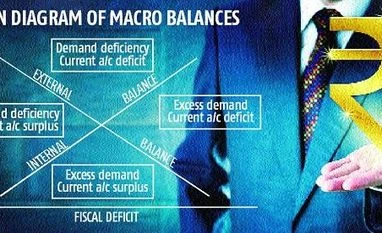

Above the internal balance line there is a deficiency of demand and below it, a threat of inflation. As for external balance, above the line relative costs and/or the fiscal deficit are at a level that would lead to a current account deficit, and vice-versa below the line. Swan’s diagram was developed for a small economy with free capital flows. Hence interest rates were assumed to be set exogenously by global conditions and the need to prevent reserve depletion.

There are some modifications one has to make to apply this framework in a global economy where private capital flows have increased manifold relative to those 40 years ago. Interest rates have become an important macroeconomic policy variable and one would want to add a third axis to the domestic interest rate. External balance would now be not just on current account but also on capital account with interest rates affecting not just domestic demand but also foreign capital flows. As for internal balance, the impact of interest rates would be not just on current demand but also on growth potential.

Applying it to Indian conditions today one could argue that we are in the top quadrant — demand deficiency and a current account deficit. Moving towards a balance requires an exchange rate policy that improves relative domestic cost advantage that boosts exports and, if that is not enough of a stimulus, then some more demand boosters would be needed from fiscal measures and an interest rate reduction (controlled enough to calm nervous foreign bankers).

The broader policy message is clear. The pursuit of macroeconomic stability cannot be based on simplistic fiscal deficit or inflation targets. Exchange rate management, the interest rate set by the central bank, the fiscal stance of the government must be set in the light of prevailing global and domestic conditions rather than be bound down by unconditional rules.

)

)