The decision to form the Ministry of Jal Shakti in 2019 was an important milestone in reforming water governance in India. It brought together under one umbrella the departments dealing with drinking water and irrigation. Ever since Independence, the governance of water has suffered from at least three kinds of “hydro-schizophrenia”: that between irrigation and drinking water, surface and groundwater, as also water and wastewater. The new National Water Policy (NWP) suggests urgent action to overcome each of these divisions.

Government departments at the Centre and states have generally dealt with just one side of these binaries, working in silos, without co-ordination with the other side. As a result, critical inter-connections in the water cycle have been ignored, seriously aggravating water problems. We fail to see the link between rivers drying up and over-extraction of groundwater, which reduces the base-flows needed by rivers to have water even after the monsoon.

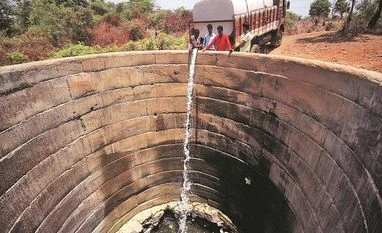

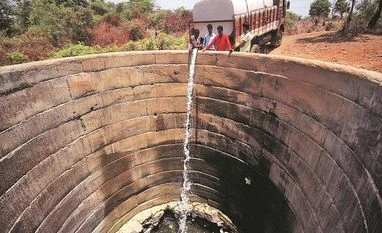

Placing drinking water and irrigation in silos has meant that aquifers providing assured sources of drinking water dry up over time, because the same aquifers are used for irrigation, which consumes much higher volumes of water.

This has adversely impacted availability of safe drinking water in many areas. And when water and wastewater are separated in planning, the result generally is a fall in water quality, as wastewater ends up polluting supplies of water.

The Central Water Commission (CWC) set up in 1945 is India’s apex body dealing with surface water and the Central Ground Water Board (CGWB) set up in 1970 is the one handling groundwater. Over several decades, even as ground realities and understanding of water have both undergone a sea change, the CWC and CGWB have remained virtually unreformed, working in pristine isolation from each other, with little dialogue or co-ordination between them.

The same pattern is visible in the corresponding bodies at the state level. Ironically, even as groundwater use has grown in significance, becoming India’s single most important water resource today, groundwater departments have only gotten progressively weaker over time.

The NWP suggests merger of the CWC and CGWB to form a multi-disciplinary, multi-stakeholder National Water Commission (NWC). The policy visualises that this exercise at the Centre would become an exemplar for all states to follow.

Bridging multiple silos, the NWC would include the following divisions, which would work in close co-ordination with each other: 1) Water Security Division to guide the fulfilment of national goals pertaining to drinking water; 2) Irrigation Reform Division to more effectively meet the overarching national goal of “har khet ko paani” (water to every farm); 3. Participatory Groundwater Management Division to ensure sustainable and equitable management of India’s most important resource; 4) River Rejuvenation Division to work towards revival of India’s river systems; 5) Water Quality Division to reflect the highest priority to be given to this aspect; 6) Water Use Efficiency Division to improve performance on this parameter in all economic activities; 7) Urban and Industrial Water Division to meet these emerging national challenges; 8) Democratisation of Data Division to ensure the development of a 21st century national water database, with user-friendly access to primary stakeholders of water; 9) Knowledge Management and Capacity Building Division to generate and disseminate knowledge on water, as also build requisite capacities within and outside government.

Both at the Centre and in the states, government departments dealing with water resources today include professionals predominantly from just civil engineering, hydrology and hydrogeology. Despite the avowed commitment to rejuvenating our rivers, we have never had a single river ecologist or ecological economist in any department handling water anywhere in India. Despite the fact that agriculture takes up most of our water, we do not have even one agronomist within the water bureaucracy.

While it is clear that water management always needs community mobilisation, water departments have never included social mobilisers. The NWP argues that the NWC and its counterparts in the states need experience and expertise in all these disciplines, without which solutions to India’s complex water problems will remain elusive. Since systems such as water are greater than the sum of their constituent parts, solving water problems requires understanding whole systems, deploying multi-disciplinary teams and a trans-disciplinary approach, as is the case in the best water resource departments across the globe.

Wisdom on water is not the exclusive preserve of any one section of society. The NWP, therefore, enjoins the state and central governments to build a novel architecture of enduring partnerships with primary stakeholders of water. Thus, the NWC, and its counterparts in the states, must include farmers, water practitioners, academia, industry etc. and build respectful partnerships with all of them, based on mutual learning. The indigenous knowledge of our people, with a long history of water management, is an invaluable intellectual resource that should be fully leveraged. The unique experience and insights of women must also be actively drawn upon.

Problems have often arisen in the water sector owing to varying and sometimes conflicting understanding, perspectives and positions on key issues, between the Centre and states, as also across states. There is, therefore, an urgent need for an institutional mechanism that facilitates constructive discussions, translating into mutually agreed actions on the ground that can at best prevent conflicts or at least find time-bound resolution for existing disputes.

The NWP suggests that this could be done either by creating a new inter-state council or by recasting and activating the existing National Water Resources Council. The council should also facilitate water reforms as per the needs of states and facilitate capacity enhancement required to implement the paradigm shift proposed in the NWP. The council should be equipped with the requisite multi-disciplinary expertise and multi-stakeholder representation, to enable it to play this role in the most effective manner.

The writer is Distinguished Professor, Shiv Nadar University. He chaired the Committee to draft the new National Water Policy set up by the Ministry of Jal Shakti in 2019

)

)