I like Republic Day more than Independence Day. We would have received independence from the United Kingdom in any case around that period. They were a nation badly affected by World War II (Indians may not be aware of how terrible a time the 1950s was for the British middle class). And the British were under pressure from America to decolonise. Independence would have come any way. It is the building of a republic that is important. And here we did brilliantly, while all around us in South Asia nations succumbed to parochialism and majoritarianism.

What do I mean by the word majoritarian? I mean the attitude that the religious majority is entitled to a certain degree of primacy. And that the rights of the minority are subject to the approval of this majority. In Pakistan, Jinnah died in September 1948. In August the previous year he had made a speech hinting that he wanted to see a secular constitution in Pakistan. Six months after his death, under his successor Liaquat Ali Khan, Pakistan declared that Allah was sovereign in Pakistan and not the Pakistani people. The substantial contingent of Hindus from East Pakistan (Bangladesh) in the Assembly objected to this but was overruled.

Pakistan declared itself an Islamic republic but it did not really know how to blend Islam into the modern state. This was not a new problem and Muslims had never been able to agree on what was the ideal Islamic state. The first schism of Islam, Shia versus Sunni, was also political.

One of Pakistan’s intellectuals, Abul Ala Maududi, the founder of the Jamaat-e-Islami, theorised that because Islam’s message was the unity and oneness of God, multi-party democracy would not be Islamic. Former prime minister Nawaz Sharif tried and failed to get a law passed (the 15th amendment) that more or less would make him a permanent ruler.

While it was struggling to build this ideal Islamic republic, Pakistan also introduced new elements into the law. These included forcing people to pay Zakat, the tax that is one of the five pillars of Islam. Banks automatically deduct 2.5 per cent of the balance in the accounts of Pakistan’s Sunni Muslims on the first day of the month of Ramzan.

Punishments like cutting of hands for theft and lashing for drinking were introduced but, for the most part, they were not implemented. The most effective way in which Pakistan could express its Islamic nature was through oppressing its minorities. Under the constitution of General Ayub Khan in the 1950s, non-Muslims were banned from holding the office of president. In the 1970s, under prime minister Zulfikar Ali Bhutto, non-Muslims were banned from holding the office of prime minister. Bhutto also passed in 1974 a law persecuting a sect called the Ahmadis, who were declared non-Muslim by the constitution (the 2nd amendment).

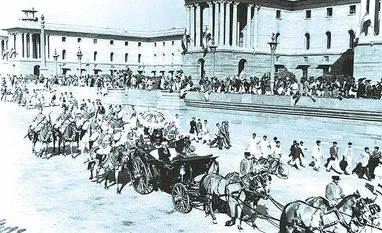

The first Republic Day parade in 1950. Our constitution is absolutely unique in South Asia because it gives no special position to Hinduism or Hindus

All South Asian nations have tried to figure out how to introduce their religious and majority identities into their constitutions. Sri Lanka’s constitution says that “The Republic of Sri Lanka shall give to Buddhism the foremost place and accordingly it shall be the duty of the State to protect and foster the Buddha Sasana”. The Sinhala Buddhist nationalism clashed with Tamil nationalism and produced disaster for that beautiful country.

Bangladesh has long struggled with its balance between religion and the Bengali nationalism on the basis of which Pakistan was partitioned in 1971. Its constitution originally opened with the words “Bismillah ar Rahman ar Rahim”. But there has been uneasiness in Bangladeshis about their identity and the Supreme Court removed these words from the constitutional text.

Today, Bangladesh politics is divided between two political forces, which fight over whether the nation or not should be anti-minority and more Islamic. The ruling party, the Awami League, is “secular” in the way that we used the word in India, meaning tolerant of minorities. The opposition BNP is anti-minority.

In Bhutan’s constitution, article 2 says that “the Chhoe-sid-nyi of Bhutan shall be unified in the person of the Druk Gyalpo who, as a Buddhist, shall be the upholder of the Chhoe-sid”. Chhoe-sid-nyi means the temporal and spiritual powers, meaning that the Buddhist king is supreme in both.

Myanmar’s constitution recognises “the special position of Buddhism as the faith professed by the great majority of the citizens of the Union”.

The Maldives constitution says the country is a republic “based on the principles of Islam” and that “this Constitution guarantees to all persons, in a manner that is not contrary to any tenet of Islam, the rights and freedoms contained within this Chapter, subject only to such reasonable limits”.

Nepal was, till a few years ago, the world’s only Hindu state. What made it Hindu specifically was that executive power flowed from a Kshatriya king (the Chhetri dynasty), as prescribed by Manusmriti. But the other aspects of Hinduness, meaning the implemented the caste system, could not be carried out because it goes against the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. In India’s constitution, articles 14-17 specifically address this and prohibit the practice of caste and doctrinal Hinduism.

Our constitution is absolutely unique in South Asia because it gives no special position to Hinduism or Hindus. In that sense it is the only modern constitution in our parts and it is the reason why we have had the least political turmoil in our country compared to the others who have meddled with majoritarianism and paid the price.

This is why I think Republic Day is a much more important day for us Indians than Independence Day.

)

)