Two views on India's first woman prime minister Indira Gandhi

Sagarika Ghose's 'Indira: India's Most Powerful Prime Minister' has hit the stands

)

Explore Business Standard

Sagarika Ghose's 'Indira: India's Most Powerful Prime Minister' has hit the stands

)

Indira: Alternative facts

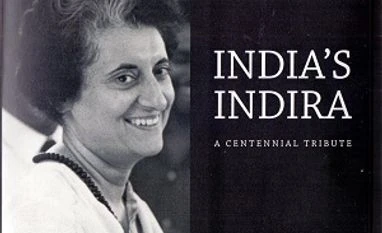

When the title of a book reads “a centennial tribute”, you know what to expect. Brought out by the Indian National Congress to commemorate Indira Gandhi's birth centenary, India’s Indira conveniently glosses over her every controversial decision and action, including the Emergency.

Already subscribed? Log in

Subscribe to read the full story →

3 Months

₹300/Month

1 Year

₹225/Month

2 Years

₹162/Month

Renews automatically, cancel anytime

Over 30 premium stories daily, handpicked by our editors

News, Games, Cooking, Audio, Wirecutter & The Athletic

Digital replica of our daily newspaper — with options to read, save, and share

Insights on markets, finance, politics, tech, and more delivered to your inbox

In-depth market analysis & insights with access to The Smart Investor

Repository of articles and publications dating back to 1997

Uninterrupted reading experience with no advertisements

Access Business Standard across devices — mobile, tablet, or PC, via web or app

First Published: Jul 14 2017 | 11:28 PM IST