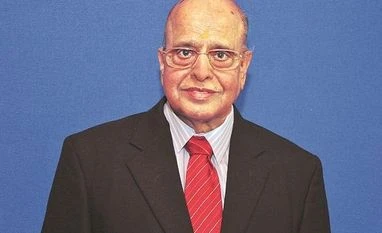

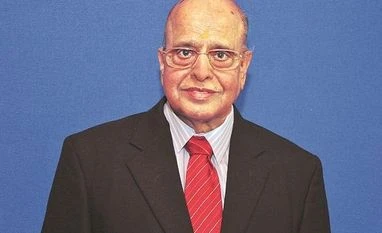

One of the architects of the new National Education Policy (NEP) 2020, former chairman of Indian Space Research Organisation (ISRO) Dr K Kasturirangan has played a pivotal role in the latest reforms in Indian education. As chairman of the Kasturirangan Committee that submitted the report that helped form the policy document, the Indian space scientist has been instrumental in making Indian education 21st century-ready. In an interview with Vinay Umarji and T E Narasimhan, Kasturirangan defends scepticism, especially around regional languages as a medium of instruction and fee cap for private institutions, among others. Edited excerpts:

In what salient ways is the new policy different from the previous one?

NEP 2020 aims to help students learn about the world around them and contribute to it in various ways by focusing on learning by doing, by developing critical thinking and problem-solving skills, along with the other 21st century literacies, competencies and personality traits. The policy, therefore, has a keen focus on early childhood care and education as well as in ensuring that students attain literacy and numeracy. There is also emphasis on vocational education that will be integrated into school and college education. Another key focus area is the vision of a liberal education that begins in secondary school and carries on into undergraduate education. There is also a provision to increase the number of researchers and the quality of research through the National Research Foundation.

How different is the new NEP from the report submitted by your committee?

Almost all the recommendations in the draft policy made by the committee have been accepted. Some, such as the new regulatory structure for ‘light but tight’ regulation has been modified for better efficiency of execution. The draft policy had recommended uncapping fees in the private sector along with the suggestion that private institutes provide scholarships to up to 50 per cent of their students. However, given some Supreme Court judgments on the issue, the government has retained the cap on fees.

What could be some immediate execution challenges of the policy that you foresee?

The execution challenges will depend a lot on the implementation plan that the Centre and the states work out. It will be important to wait for those before assessing the challenges.

There has been some scepticism around local language teaching till Class V in the NEP.

We must not confuse learning languages with the medium of instruction. The policy is clear that as a country we must not deny children the advantages of knowing English. Therefore, English must be taught extremely well to all children in all schools, and especially so in those schools where the medium of instruction until Grade 5/ 8 is in the mother tongue/local language/regional language. Schools can continue to advertise their medium of instruction for the benefit of parents. However, parents also need to understand the issues regarding language learning. They would like their children to learn English well, starting at a very young age, but this does not happen only by having English as the medium of instruction. There is no compulsion on schools to change their medium of instruction. This is only a strong recommendation to use home language/mother tongue/local language to teach very young children.

While graded autonomy has been a much-needed move, many colleges fear losing affiliation and facing even closure. Are these fears justified?

There are many poor-quality colleges in the country. Besides learning from teachers, students also learn a lot from each other (peer learning). Yet most Indian colleges do not provide the environment for learning since they are very small, have low enrolments, and also do not have any residential facilities.

)

)