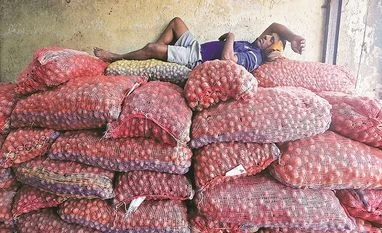

With potato prices crashing on account of a bumper production, the West Bengal government’s move to fix a minimum support price (MSP) for the crop is unlikely to bring much cheer to farmers in the state.

At a recent farmers’ meet, chief minister Mamata Banerjee blamed demonetisation, along with the bumper potato production, for the price crash.

On Tuesday, the state government announced the MSP of Rs 460 a quintal, or Rs 4.60 a kg, for procurement of potato to salvage farmers reeling from the price crash.

The government will procure about 28,000 tonnes of potato over the next few months for mid-day meals in schools. However, against a production of about 11 million tonnes this year, the government’s procurement would account for less than three per cent of total production. Last year, West Bengal produced about nine million tonnes of potatoes.

Nevertheless, potato prices recovered marginally after the government’s announcement. The prices went up from Rs 320-380 per quintal last week to about Rs 380-430 per quintal in open market. Yet, the prices are below the cost of production, which comes at Rs 450-500 per quintal.

Against the production of about 11 million tonnes this year, local consumption is not more than 5.5 million tonnes. The state generally sends about 4.5 million tonnes of the commodity to neighbouring states. The state is left with a surplus of one million tonnes, leading to a price crash.

Apart from fixing the MSP, the government will provide transport subsidy to facilitate exports. The subsidy will be to the tune of 50 paise a kg for railways transportation and Rs 1 a kg for shipments outside India.

While a handful of rich farmers in the districts of Paschim Medinipur, Barddhaman and Hooghly can pay for transportation and the rent for cold storage, small farmers in West Bengal sell their produce to middlemen.

With a contribution of 25 per cent in India’s potato output, West Bengal is the second largest producer of the vegetable after Uttar Pradesh.

Inadequate marketing channels, manipulation by middlemen and the absence of support prices make potato cultivation in the state inherently risky.

)

)