Watching some of Williams’ last practice session of two hours before the final was to imagine her as an Amazon incapable of retiring. Even so, she looked noticeably a few steps slower, understandable as it is only 10 months since she gave birth to a baby girl. Last Saturday, she was duly trounced by the variety and aggression of Angelique Kerber, who moved her around and made her heavy-footed. Perhaps this is a rivalry that could keep Williams in the game for another couple of years.

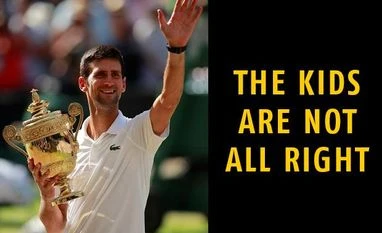

The reigniting of the Djokovic-Nadal rivalry certainly rekindled the Serb’s love for the game in the semi-final. Watching the Serb this year had hitherto been akin to watching the meltdown of a modern-day Hamlet, albeit one with many monologues and little poetry. Just weeks ago, after losing to an unheralded Italian at the French Open, Djokovic looked mentally unhinged, refusing to appear in the main interview room and declining to answer questions about whether he would play the grass-court season at all. In the early rounds at Wimbledon, he seemed to be “playing from memory”, as Martina Navratilova put it. Then, facing the anything but stiff- upper-lip Centre Court crowd in his match against the Brit Kyle Edmund, Djokovic was unfairly booed for questioning a decision by the umpire. I was courtside and have never seen anything quite like it; the umpire somehow made three incorrect calls on a single point and a jingoistic crowd turned on the victim. In this case, they did Djokovic a favour.

They stoked his competitive fire and, equally importantly for a man who keenly feels he does not get his due relative to Federer and Nadal, appeared to make him impervious to the need for crowd support. This kept him going through the see-sawing semi-final with Nadal, who now suffers a mental block playing the Serb. Those who want tennis’ Grand Slams to institute a tie-breaker at 6-6 will use the disappointing final as an emblem of the need for change, but Djokovic by then was unbeatable. Anderson, subject to fatigue and the same attack of nerves he suffered in last year’s US Open final, which he lost to Nadal by a similar scoreline, certainly was not the opponent to pull off an upset. He did not venture to the net much and had done so only 50 times in the big-serving contest with Isner, a match in which most points were decided by baseline duels. In that sense, the battle of the giants was an emblem of how uncomfortable at the net even today’s big servers are, in part because they do not make the journey often enough but primarily because the heavy power top-spin generated by today’s racquets and strings makes volleying so difficult. That was former Wimbledon champion Stefan Edberg’s assessment when I asked him last year why the style of play he, Boris Becker and McEnroe had perfected had gone out of style.

)