Beyond boundaries

The Danish Girl celebrates sexuality in the most extraordinary ways

Manavi Kapur If an Indian middle-class man walks into the movie hall without knowing what

The Danish Girl is about, it could be a shock to his entire belief system. This was certainly the case with a friend who graciously agreed to watch the film with me. In a country where cross-dressing men are often seen only in comic settings - a la

Comedy Nights With Kapil - a film about a man's journey to womanhood can be a jolt. Releasing just a week before the bizarre "porn comedy"

Kya Kool Hain Hum 3, Eddie Redmayne- and Alicia Vikander-starrer

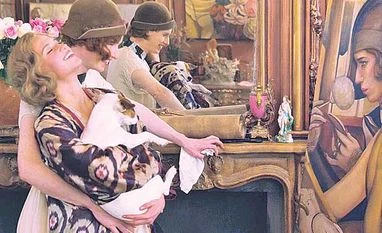

The Danish Girl is a celebration of female sexuality in ways one rarely gets to see. Based loosely on the lives of Danish artists Gerda and Einar Wegener, the film follows the story of what the couple goes through after Einar (played masterfully by Redmayne) discovers he is a woman "inside".

In 1920s' Copenhagen, a world before society formulated and accepted the idea of cis-males and -females, Einar explores the boundaries of his sexuality with a heart-wrenching mix of hesitation and boldness. It all begins with an innocent episode, where Gerda, an artist struggling to come out from under her husband's successful shadow, asks Einar to sit for a painting because the model is late. Einar wears a woman's sheer pantyhose and dainty shoes, holding up a gown for effect. Clothes become a metaphor of sorts through the two hours of the film, a tangible expression of the internal conflict between Einar and Lili Elbe, the woman he eventually transitions into. Einar is fascinated with the softness of women's clothes, caressing pantyhose and gowns with a gentleness that he finds surprising. In a particularly breathtaking scene, he wears Gerda's satin gown under his shirt and trousers, which both he and Gerda find arousing.

Though it begins as a joke, Einar soon starts observing the mannerisms of women and the lines between play-acting and reality begin to blur. Gerda, who sketches Einar in his sleep, also becomes Lili's creator. Einar's life becomes a mirror of Gerda's portraits of him, unshackling his femininity and, with it, Gerda's artistic prowess. Gerda, too, portrays the troubled wife and artist with elan, losing a husband but finding a friend and her muse. A hat tip to Vikander for a layered portrayal of Gerda, who oscillates between being the staunchest supporter of Lili's sexuality and a wife mourning the loss of her husband.

The film is clever in its themes, presenting the idea of male and female gaze in the subtlest possible ways. The metaphors abound in every scene, including a simple nose-bleed that is a pseudo-menstrual cycle for Einar. The hospital is a metaphor for sanity and insanity, one where Einar escapes from and another where Lili finally finds a life. The scarf Lili buys for Gerda is an expression of Lili herself, who is finally set free in the concluding scenes of the film.

Director Tom Hooper replicates his delightful ability to flesh out a period in history through the colours and textures. The background score is at once soothing and surreal, blending perfectly well with the central plot. Redmayne is the true star in the film, both as Einar and Lily, outshining anyone else he shares screen space with.

The Danish Girl is a poignant film ahead of its time, offering an intricately woven tale of sexual liberation. It remains behind perhaps only in being race-blind, with just one man of colour throughout the film. But while the film is set in an era on the edge of the modernist movement in Europe, its subjects are on the brink of a postmodern world, forever in flux and celebrating the pluralism in the most extraordinary ways.

)

)