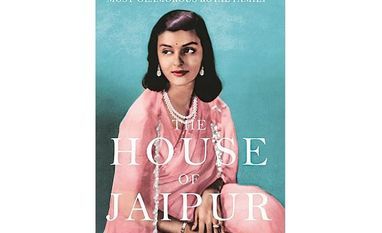

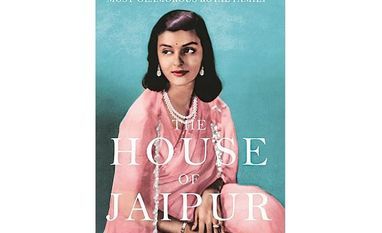

We grew up with possibly apocryphal but definitely slanderous stories of Gayatri Devi, who, it was rumoured, had snatched her mother’s love interest to marry Sawai Man Singh II, becoming Jaipur’s Third Her Highness in the bargain. While his senior maharanis drank themselves into oblivion, her own brothers fared little better. Racy gossip skittered around the edges of her chiffon sarees, her coiffed head of bobbed hair, and her lifestyle, while her contributions to the arts and education were swept under the carpet. Gayatri Devi was a diva who hobnobbed with Queen Elizabeth, Jackie Kennedy and Hollywood A-listers, the “tomboy” in her delighting in horses and shikar, the princess loving the accoutrements that came from being painted by European artists, photographed by Cecil Beaton, the jewels, exotic holidays and pageantry.

I first met the Rajmata as her ghost-writer for an illustrated book. Our meetings were arranged at a dowdy government bungalow in New Delhi, its interiors salvaged by silk carpets and silver doo-dahs. On one occasion, she introduced me to her son Jagat, then promptly ticked him off for plonking himself in our midst. Her step-son, Maharaja Bhawani Singh, whom I interviewed at the height of their internecine feud for another project, made it clear they did not see eye-to-eye. When the manuscript was published, Gayatri Devi pounced upon a printer’s devil as my denouement — freezing my greetings with glacial scorn when our paths crossed.

John Zubrzycki’s book places Gayatri Devi — or Ayesha, as he refers to her throughout the book — in the midst of the Jaipur dynasty’s litigation, blaming the late maharaja for dying intestate on a polo field in England. The Kachchwaha family controversially progressed by establishing relationships with the powers in Delhi, whether the Mughals, the British, or the Congress, adding considerably to its prestige and wealth. Zubrzycki — no stranger to India, having previously authored other books here — sets out to mine the princely kingdom for historic facts as well as trivia. But his heart is not in the archaic data as much as in the lead-up to the scandals and innuendoes surrounding the family. He manages this by walking the fine line between history and libel while ensuring he does not stray too far from the family’s recent travails. (Disclaimer: I was interviewed by Zubrzycki for this book.)

While Man Singh — or Jai, as he was popularly known — managed his interests and those of his family, his sudden end threw open the proverbial can of worms. He had sons from all his three wives, palaces for the picking, unimaginable wealth and a vindictive prime minister determined to put the royals in their place. During the Emergency Ayesha found herself imprisoned amidst prostitutes and petty thieves in Delhi’s Tihar Jail while revenue officials had a field day digging for hidden treasure in Jaigarh Fort — alas, in vain.

Zubrzycki’s recent history is familiar ground for anyone with a passing interest in princely affairs but is, nevertheless, compelling: Jagat, Gayatri Devi’s son, too leaves behind no will, though one is later discovered in which he disinherits his estranged children born from an alliance with a Thai princess. Ayesha’s distancing from them, and later patch-up, helps them gain part of their rightful share — only, no one seems to know quite what that includes. There are the unseemly wrangles in the family of First Her Highness too. Her eldest son Bhawani Singh’s daughter married the man she loves even though he is a “commoner”, and of the same gotra, then adopts his first grandchild — the dashing Padmanabh Singh — as his heir and Jaipur’s notional maharaja, thereby breaking the creed of primogeniture. His second grandson is adopted by his wife’s family as maharaja of Sirmour. Ironically, his daughter has since divorced. The sons born to the Second Her Highness face their share of litigious ignominy.

)

)