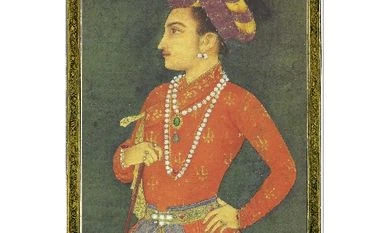

Shah Jahan with his ‘favourite’ son, Dara Shikoh, in this painting taken from a leaf of an album made for Shah Jahan in 1620

Well-prepared with carefully written notes, Chandra wears the expressions of the archetypal professor who intersperses the rich and well-researched text with witticisms to keep his audience attentive. For him, the importance of Dara Shikoh lies in the various cultures he sought to represent. “The Mongol, Chagatai Turkish and Iranian traditions all converge in the Mughal dynasty. Dara was, in many senses, a direct successor of his great-grandfather Akbar’s spiritual legacy,” he says.

Where Akbar tried to create a parallel religion, Din-i-Ilahi, which incorporated the best principles of Hinduism, Christianity, Islam and Sikhism, Dara Shikoh translated many of the Upanishads and Vedas from Sanskrit to Persian. “In fact, it was Dara Shikoh’s translation that eventually helped Anquetil du Perron, the French Indologist, to translate 50 Upanishads into French. This, in turn, helped formulate the thought behind structuralism, which greatly influenced European thought,” says Chandra, eyes gleaming with the glee that a grandparent might have while narrating a story to young children.

But this gleam dims a little when the mention of religion comes up. “Dara Shikoh should be revered for his ideas and concepts. The moment you bring in any religion into the question, the argument becomes more complex,” he says.

The question Chandra tries to avoid is whether Dara Shikoh was as revered among pious Muslims as Aurangzeb. For history suggests that the two brothers were starkly different in their approach to Islam: while Dara Shikoh believed in a more “open” and accepting religious identity, Aurangzeb is believed to have followed Islam by the book.

“Only a fringe minority of Islamic hardliners do not recognise Dara Shikoh’s work and legacy. He was otherwise quite popular among Hindus and Muslims,” says Firoze Ahmed Bakht, grand-nephew of Maulana Abul Kalam Azad. Dara Shikoh thus stands as the beacon of Hindu-Muslim unity, an emperor who many believe could have even averted Partition. This thought is shared by thinkers across the border, too. Shahid Nadeem, a Pakistani playwright, discusses this trope in his play Dara. “The ‘what if’ question has a mixed bag of answers. But I do believe there would have been more peace had he ascended,” says Bakht.

)

)