In a school, a short distance away from where the annual Sawai Gandharva festival is held in Pune, a small group of musicians is talking to a classroom full of boys and girls about Indian classical music. Had they heard of a singer, perhaps, or about an instrument? A young boy raises his hand. His reply: Honey Singh.

The answer hits Mandar Karanjikar, the man asking the question, like a whiplash. But it is not really a surprise, says Karanjikar, an engineer and a classical vocalist: if the children don’t hear classical music, how will they know it? Mandar, along with Dakshayani Athalye, has set up Baithak, a not for profit in Pune to “promote classical music in all sections of the society, irrespective of socio-economic background”.

Groups such as Baithak are springing up in every city and a fair number of institutions and corporate donors are involved in the support of Indian classical music. Yet, spaces and audiences for amateur performances are shrinking.

Suvarnalata Rao, programming head of Indian music at the National Centre for Performing Arts (NCPA), Mumbai, says it is important now more than ever before to bring young, fresh out of their training musicians on to public platforms.

NCPA, she says, has one of the oldest programmes for promoting young artistes. The latest one is the Citi-NCPA Promising Artists Series that supports eight gurus and their (three each) shishyas. The gurus are looked after under the programme and they do not charge the chosen students. One of the artistes being trained under the scholarship is Rageshri Vairagkar who says that this is a boon for musicians like her who spent every waking hour thinking of music. “I know that it will take time to be a great singer but I am only happy when I am doing my riyaz,” she says.

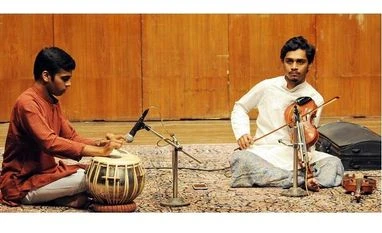

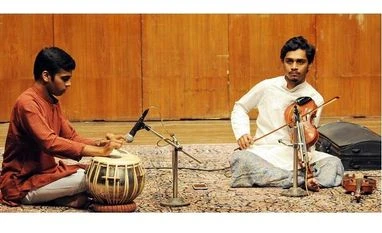

Young artistes performing as part of the Baithak series

Rao says, “Most of the time they (first-time performers) do not have listeners. They are not brands.” The problem is not new as Rao points out, but the situation is more critical because there are more young musicians coming out, trained by a set of well-established and proficient gurus. The opportunities and the platforms that support them have, however, not kept pace. Patrons prefer established vocalists and instrumentalists and hence give the young artistes a miss and also many of the performances are located at city centres, while the audiences mostly live in the suburbs.

It turns out to be a vicious cycle, says Karanjikar. Not getting a space to perform reduces the chances of music as a career option, disheartens the artiste and forces her to turn to alternative sources of income. Baithak organises musical soirees in people’s homes or at select venues and is funded through donations. He says, “There are so many new musicians — 15 to 20 good disciples are coming out from every guru and there is no patronage. You need some income and you cannot always self-fund a musical career.”

Young artistes performing as part of the Baithak series

Does every musician need a stage? And a live audience? What about the growing influence and spread of digital platforms in the country? A live audience is a must, says Rao who has spent 28 years in the business of Indian music. (Classical, she says, is a misnomer, a label the British stuck on the form. Classical refers to a period, while the Indian traditions are oral and more fluid and not pinned to a timeline.) “There is a quality that art expects and it takes time for a performer to come to that level. In an oral tradition, improvisation is important, it has to be a part of the training. That is why young artistes need so many performance platforms. To be able to improvise in front of so many people, they need concerts.”

Finding a platform, however, can take a lifetime. Stories about the harrowing experiences of young artistes are common lore. One young teacher of Hindustani classical music suffered a nervous breakdown because she could not find any place to perform and her guru refused to support her. It has taken her years to get back to her music. Another talks about how she spent several years waiting in recording studios, only to be told about a music director’s protégé being given a chance to audition over her. She now uploads her music on YouTube and performs at small gatherings at friends’ homes. It is nowhere as fulfilling as singing in front of an audience or making a career out of it, she says.

Rao says the plight of the young artiste has always been a matter of concern for promoters of the arts. The first director of the NCPA was

P L Deshpande. He created an endowment for up-and-coming artistes. Artistes were taken around the state, giving them the exposure and audiences a taste. “Today, big donors want big names; they are not always happy to promote upcoming artistes,” says Rao.

It is not just patronage that has changed. Audiences have too. They don’t want to or are unable to travel to the performance centres. Shrinking of the audience is a challenge, but Karanjikar says this is not because people are uninterested. Some are uninformed and sometimes it is just a matter of logistics. People now live far away from the places that offer such music. Baithak, he says, has found incredible support from people. From his house, the soirees have moved to several homes and they also work with three municipal schools and two construction sites. “The children love the music wherever we play,” he says.

Early exposure could change the situation, says an amateur musician based out of Mumbai. She says that the big challenge is in the way music is packaged for the audience. “A lec-dem on dhrupad, for instance, will draw people in but a pure khayal programme may not,” she says. Also, there are fusion concerts that are sold out in the city even as pure classical music concerts stare at empty aisles.

NCPA is also working with schools to build audiences. “We have adopted 20 schools. By teaching, we are hoping for engagement with young students,” says Rao. They also train teachers and provide them with ideas on how to include music in the classroom.

So, perhaps the next generation of musicians does have something to look forward to.

)

)