Will they, won’t they? While the Reserve Bank of India (RBI) has started reducing interest rates, banks are reluctant to oblige and have ample justification to do so; just when interest rates on Employees’ Provident Fund (EPF) have been hiked.

Lack of transmission in policy rates is not a new debate, nor will it end anytime soon. Unless banks cut their deposit rates, they cannot lower their lending rates. And if lending rates are not lowered, any amount of rate cut by the RBI is likely to be wasted. The repo is a signal rate, and not the final rate, controlled by banks, for the economy.

In an economy, rates depend mainly on three factors — inflation, liquidity in the banking system and government’s fiscal position that has a direct bearing on market borrowings.

Currently, inflation is at around 2 per cent, and therefore this merits lower interest rates, precisely what the central bank has done.

But for banks to follow up with the rate cut, the system has to have surplus liquidity where the banks don’t have to chase depositors to get funds. As on February 21, the system liquidity was in deficit of Rs 1.34 trillion.

This is hardly conducive for a bank to cut rates because not only do banks struggle with liquidity, but bond yields, a crucial component in the marginal cost of funds-based lending rate (MCLR) calculation, also rise.

Then, there is also competition for deposits. Pallab Mahapatra, managing director and chief executive officer of Central Bank of India, said deposit rates cannot be lowered any more as that would make his bank vulnerable to poaching for deposits from competing banks. And this, therefore, makes transmission a challenge.

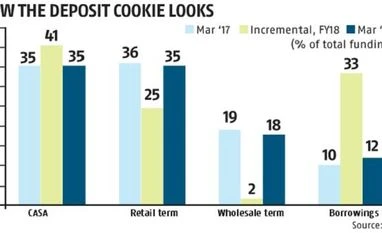

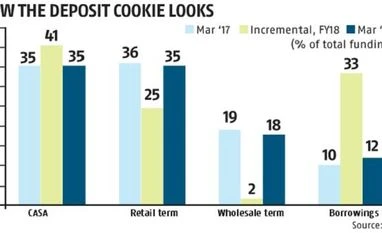

According to foreign brokerage CLSA, even as the share of low-cost current and savings accounts (CASA) has improved due to more financial inclusion, digitisation and demonetisation, retail term deposits are coming down for the banks “given the deepening presence of alternative investment avenues such as mutual funds/insurance and their tax efficiencies that enhance post-tax returns by 1.5-2 percentage points over bank term deposits”.

Banks are also faced with a unique problem.

On one hand big companies are piling up bad debts, and banks are entering into standstill agreements with them to delay their repayment obligations, and at the same time, credit is growing much faster than the deposits.

Ahead of the election, currency in circulation (CIC) is over Rs 21 trillion, above the levels seen pre-demonetisation. The year-on-year growth in CIC is also at 18 per cent, compared with the normal 13-14 per cent.

Higher cash means the money is getting out of the banking channel, creating a liquidity tightness. High credit deposit (CD) ratio, with incremental CD ratio over 100 (indicating credit disbursement is more than deposit mobilisation) leaves banks no room to cut lending rate.

“The entire system is back to bank loans. Banks are giving loans to non-banking financial companies (NBFCs) as the market doesn’t trust them much anymore. We urgently need refinance support from the government. The contribution of the government in export refinance and other such windows is very low,” said the banker quoted above.

The fight for deposits is happening at a time when low-cost current and savings deposits are steadily coming down in the system, whereas banks are setting aside larger sum of money to take care of their deposits.

With inputs from Abhijit Lele

)

)