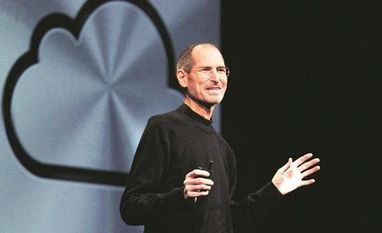

Silicon Valley has a perception problem. Steve Jobs once said, speaking about the irreverent culture he helped create, that “it’s better to be a pirate than join the navy”. This ethos served the community well when its firms existed at “pirate scale”. But now Silicon Valley’s most successful companies have become some of the largest in the world. This culture must accept that it has become the navy, with its remaining pirates facing a choice — enlist, or walk the plank.

Perhaps no company is struggling with this reality more than Google. Founded in 1998, the company famously adopted the motto “Don’t be evil” around the year 2000. Ever since, whenever the company has run into controversy, such as its censorship disputes with China, or its recent decision to fire the author of a controversial 10-page memo, critics have lashed out at the company over its betrayal of its founding values.

But it’s not fair to hold Google, or its parent company Alphabet, to the same principles it adopted when it was a relatively inconsequential technology start-up. In 2000, when it adopted “Don’t be evil”, Google had revenue of just over $19 million. In 2017, it will have revenue of over $100 billion. That’s higher than the gross domestic product of a dozen states. Google dropped the “Don’t be evil” motto in 2015.

Google is by no means alone in being a large technology company struggling to balance historical “pirate” cultures with growing responsibilities as powerful corporations. Facebook has gotten in trouble for allowing “fake news” on its platform, influencing the 2016 election. Twitter has struggled with harassment and hate groups. And Uber has clashed with regulators, its drivers, and the impact of its internal culture on women.

Silicon Valley has a lot of self-interested reasons for preferring to maintain a facade that its culture is special, and that its industry is more innovative, virtuous and productive than every other industry. It serves as a great recruiting tool as the region competes for talent with other industries and areas. It allows insiders to maintain outsize control of their companies. And it is a way to prevent regulators from coming in and regulating Silicon Valley to the extent that it might otherwise seek to do.

But it’s time to drop the pretence that Silicon Valley deserves special treatment. Facebook and Google are content and advertising companies, digital evolutions of print and television companies that came before them. Amazon’s core e-commerce business is just a digital Walmart. Apple’s iPhone product cycle, with its annual incremental improvements, has parallels to the personal computer industry in the 1990s or even the Detroit “Big Three” automakers in the 1960s. They deserve the same scrutiny from regulatory and labour watchdogs that their old-economy peers get.

They shouldn’t have multiple classes of shares that deprive investors of voting rights. Tesla and Amazon both show that investors are willing to look past a lack of near-term profitability if they believe in a company’s vision.

© Bloomberg

)

)