In April last year, then Reserve Bank of India (RBI) governor Raghuram Rajan described the Indian economy as a one-eyed king in the land of the blind. He was speaking in the context of India becoming the fastest-growing economy despite a gloomy condition around the world. A year and a half later, India’s macroeconomic indicators no longer seem appealing even as the world economy sees a strong rebound in both economic growth and trade.

“The recovery in India’s economic growth post the 2013 currency crisis wasn’t absolute but we were only better off compared to other emerging economies, which were struggling with flat to negative growth. Now, our domestic and external macroeconomic indicators are worsening even as they improve for most of the world,” says Devendra Pant, chief economist, India Ratings.

Economic growth in India slumped to a six-quarter low of 5.7 per cent during the April-June 2017 quarter and the country is no more the world’s fastest-growing economy. Indian economy is now an outlier as most emerging economies are now showing an acceleration in economic growth either due to gains from higher commodity prices (Brazil, South Africa, Indonesia or Russia) or due to faster export growth (Vietnam, Bangladesh and the Philippines, among others).

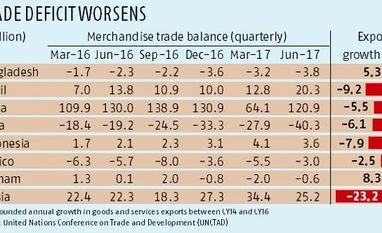

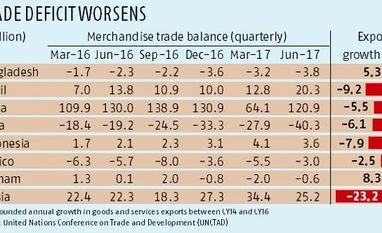

There has also been a steady deterioration in India’s external sector due to a mixture of sluggish export growth and faster growth in imports. For example, India’s deficit in merchandise trade doubled in the last one year around $40 billion during the April-June 2017 quarter from $19.2 billion during the corresponding quarter a year ago. The result has been a sharp rise in the country’s current account deficit to 2.4 per cent of gross domestic product (GDP) during the June 2017 quarter compared to less than one-tenth of a per cent a year ago.

The external sector has worsened despite benign crude oil prices for over two years now. A sharp decline in crude oil and commodity prices in international market beginning second half of 2014 provided a revenue windfall to the government and pushed up operating margins for the Indian manufacturing sector, which benefits from lower oil prices. India’s import bill declined sharply and there was an improvement in the current account deficit. Now the cycle is reversing as metal prices are up already and crude oil prices are showing initial signs of a price rally.

This raises the risk of India losing its status as the favourite destination for foreign portfolio investments. “Post 2013 currency crisis, India was the top destination for global institutional investors as it offered a combination of a steady domestic growth and stable external economic environment. This is now at risk due a steady deterioration in India's macroeconomic parameters at a time when other economies are showing improvement. This could lead to capital outflows putting pressure on the rupee and current account deficit,” says G Chokkalingam, founder and managing director, Equinomics Research & Advisory.

Some of the impact is already visible with the depreciation in the Indian rupee in recent weeks and the sell-off by foreign portfolio investors (FPIs) in the equity market. FPIs were net sellers on Dalal Street for the second consecutive month in September this year and analysts fear more exits given uncertainty about India’s economic trajectory going forward.

“Bulk of the FPI inflows into India in 2017 came in the debt market attracted by higher interest rates and a stable exchange rate. Now the combination is under threat due to recent depreciation in the rupee and the rise in current account deficit,” says Dhananjay Sinha, head of research, Emkay Global Financial Services.

“There is a high probability of government using fiscal stimulus to boost economic growth given few other sources of demand right now. It could lead to higher bond yields and lower rupee but what other option do we have right now,” asks Sinha.

Foreign investors and domestic investors who have made money in the last one year, however, may not like this even if it boosts economic growth and corporate earnings in the short term.

)

)