The Bihar election is over. Not surprisingly, it attracted money and muscle. A sizeable proportion of the assembly will now be dominated by MLAs with dubious backgrounds. What is worrying is that these proportions are rising. The issue is: does the electorate reward such choices? Or are the candidate nominations forced upon them?

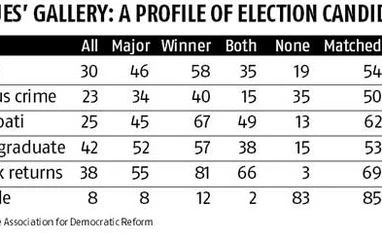

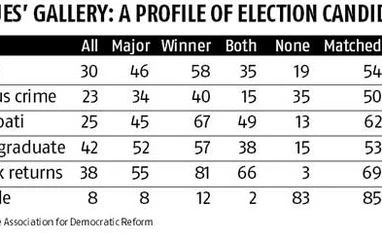

The Association for Democratic Reform (ADR) has published the backgrounds of the candidates who contested and won in the Bihar election. We present them in Table 1. Overall, 3450 candidates fought; 30 per cent of them had criminal charges against them, 23 per cent had serious criminal charges, 25 per cent were crorepatis, 58 per cent had not completed graduation, 62 per cent had not filed Income Tax Returns and only eight per cent were women. From the table it is evident that major political parties are more likely to give tickets to crorepati candidates , or candidates with criminal charges (serious or otherwise) than other parties. This is the genesis of the argument that elections in India attract money and muscle power.

Looking at the winners, it now appears one is almost twice as likely to win an election if he has a criminal charge (serious or otherwise) against him and about 2.5 times more likely to win if he is a crorepati. The most obvious response is that crime pays, as does bringing money to the election battle. Stretching the argument, it helps to be educated and file ones taxes regularly - and, in what can perhaps be seen as a welcome outcome, being a woman helps too! These observations are not new. This was true in the 2014 general elections and the two previous Bihar assembly elections.

Academic research has offered up various reasons as to why voters may prefer such candidates. In a paper published last year using simple game theoretic framework we predicted that more often than not, parties would like to match each other. For example, if the candidate nominated by B had criminal charges against him, party A will nominate someone similar; if party B nominates someone who is 'educated', so will party A.

Nowhere was this more obvious than the Bihar 2015 assembly election. This election was a two-coalition contest. We find that, in 35 per cent of the seats, both alliances placed candidates with criminal charges, while in 19 per cent of the seats, both of them had nominated clean candidates. This means that in 54 per cent of the seats the candidates were matched. Going through the list, it is evident that in most cases parties match each other.

Given this scenario, what choices are the voters left with? The last column in the table, E(P), denoting the expected proportions, answers this. It states what one would expect if the voters were to vote randomly, without displaying any affinity towards any attribute. The comparison between the E(P) and 'winners' gives us some insight into what the voters choose. Thus, if the entries under E(P) exceed the winners column, it can be construed as the voters not liking that particular attribute and vice versa.

Consider the candidates with some criminal charges. In 35 per cent of the seats both candidates had criminal cases, implying at least 35 per cent of the seats will have MLAs with some criminal charges. Similarly, there will be at least 19 per cent of MLAs who will be clean. In the remaining 46 per cent of seats, there is only one candidate who has criminal charges. If the voters voted randomly, they would on average choose about half of the candidates from these unmatched constituencies who had criminal charges while the other half would be clean. In all, therefore the expected proportion of MLAs who would have criminal charges would be 35 per cent + 23 per cent, or 58 per cent. What is the percentage of MLAs in the currently elected assembly with criminal charges? It is 58 per cent, the exact match! The same is the case with candidates who have serious criminal charges against them : it is 40 per cent. For all the attributes, E(P) is close to the winner's percentage for that attribute.

As far as money and muscle power are concerned, an average voter is not choosy - they randomise. The fact that we see more MLAs in the Assembly with these attributes is not necessarily because voters inherently like candidates who have money or muscle power but for the fact that the voters are not given too many alternatives.

It appears that the only attribute that matters is that the average voter in Bihar prefers women candidates! This can be seen from the fact that the actual percentage of women MLAs exceeds the expected percentage substantially.

Of course, one can argue that the parties had correctly anticipated this and their nominations reflected the same. However, the point remains: amidst all the excitement and gloom post election, the popular rhetoric that the voters deserve the MLAs they got (especially ones with criminal records and with money power) is to be taken with a pinch of salt.

The writer is a professor at Great Lakes Institute of Management, Gurgaon

)

)