The Indian media and commentators discovered last week that even Bharat, that is rural India, would suffer from demonetisation. They believe it will likely have a severe impact specifically on rabi crops (especially cash crops) and the rural economy in general.

There is no gainsaying the slowdown already in evidence, but my view, based on long years of study and observation of the sector, is that these fears are perhaps overly alarming. This is because of two reasons: first, most commentators, including learned ones such as Dr Manmohan Singh, generalise on the basis of a priori textbook templates. Second, the belief that informal economy is all cash does not stand scrutiny. It is a lot bigger and more complex than the cash economy, with its own finance, supply and marketing systems that function outside both formal and cash economies.

One may nurse misgivings, even serious ones, as this writer does, about the intent and the execution of demonetisation. But the analysis of its consequences must be dispassionate, factual and in historical context. So here are some common apprehensions and their possible explanations.

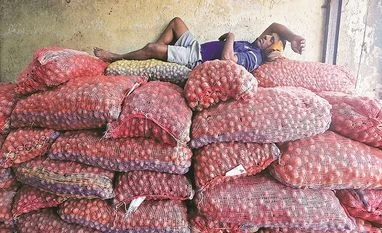

Temporary Lull: A labourer sleeps on sacks of onions while waiting for customers at a wholesale market in Mumbai last week. Fears of the positive impact of the record kharif harvest turning negative are overstated. Courtesy: Reuters

Is there an agricultural slowdown? The two most important perishable staples of daily consumption, vegetables and milk, are almost entirely cash driven. The stark picture of the deserted Azadpur Mandi in Delhi, usually a buzzing beehive, suggested that markets have ground to a halt. That was on the first couple of days of bank and ATM closures and utter confusion. But since then, reports of market arrivals and prices suggest adherence to normal cyclical trends. I saw no panic, not even a dent in arrivals, nor abnormal prices, in my two visits in this period to the local semi-wholesale vegetable market situated in a major growing area. The same is the case of milk. There are no reports of dairies stopping purchases of liquid milk, or shortfalls of supply. The country’s largest dairy distributor, the Gujarat Co-operative Milk Marketing Federation, confirms this and welcomes demonetisation which will help the cause of making payments for milk through banks. Sales of products such as butter, cheese and ice cream, which account for less than a third of the sector output, initially fell by about 20 per cent, as consumers deferred discretionary cash purchases to preserve their liquidity. They have since recovered.

What about rabi sowing?

Dire reports of farmers lacking cash to buy seeds and the belated acceptance of old notes for input purchase being restricted to government and co-operative shops have caused fears of a substantial drop in the rabi harvest.

The reality is that except for hybrids, seed replacement rates are well under the recommended 20 per cent annually. That means for most crops, a very large chunk of the seed used is home-grown. Other inputs already have long credit cycles. Further, not all input purchased from private shops are against cash. Non-formal sources — read traders and moneylenders — still account for over 40 per cent of agricultural credit. That proportion is even higher for smaller peasantry. No farmer would like to lose a sowing season. In all likelihood, smaller farmers will get into longer credit arrangements with their private suppliers, while larger farmers will supplement this source with surplus income from kharif. Labour, too, would likely be paid in instalments, as well as in kind in the form of grain, with promise of cash payments when the situation eases.

The most probable impact of demonetisation will be extension of credit periods throughout the value chain, whose bulge will reduce and gradually return to normal when full liquidity is restored, within the next two to three months. That implies only a small (if that) dip in the crop output.

Would the bonus of the bumper kharif crop vanish?

Fears of the positive impact of the record kharif harvest turning negative are also similarly overstated. Most of it, if not all, was harvested before November 8. Contracts for purchase (largely informal) have already been entered into for bulk of the unsold crop. Parties to such contracts know well the costs and consequences of reneging on them. So outstandings owed to farmers and suppliers will be stretched, but not defaulted. The impact on consumption will be a delay, but not sacrifice. Postponed consumption generally shows a rise in what would otherwise have been the volume, with attendant multipliers. So the overall consequence will most likely be that of a delay in consumption, followed by a binge.

Why are co-operatives bypassed?

For this, much blame lies with co-operatives and their leadership. The two Vyas Committee reports (2000 and 2004) on rural credit highlighted numerous fault-lines of the system and concluded that this very delicate structure is unlikely to be able to absorb major shocks. Many of the measures for prudent restructuring of rural credit recommended by these reports have met with stubborn resistance from the stakeholders (read rural politicians), who are now crying themselves hoarse over the plight of farmers.

So what could be the net impact?

The delays and disruptions are in plain sight. They could be grievous, as was the case of a Kerala farmer committing suicide because he feared his savings in the co-operative bank were lost forever. Landless labour would suffer greater destitution, even if temporary. But far more important and longer lasting is the possibility that the stranglehold of the moneylender-trader nexus on the rural economy will be strengthened due to this crisis. The trend toward greater recourse to rural institutional credit has already been reversed in the previous decade. That may gain further traction with the currency restrictions.

India’s agricultural economy and its farmers have withstood much worse — two consecutive droughts and severe crop damage due to unseasonal weather in just the last two years. The impact of demonetisation would be far smaller in comparison.

The author was a professor at the Indian Institute of Management and founder-director of the Institute of Rural Management, Anand

)

)