According to McKinsey’s ‘Digital India’ report of 2019, the benefits of digitising India are impressive, although only 40 per cent of the population has internet access, and there is uneven adoption in businesses, leaving considerable room for improvement. Yet, newly digitising sectors have experienced tremendous gains. For example, in logistics, fleet turnaround time has been reduced by 50 to 70 per cent, and digitised supply chains helped companies reduce inventory by 20 per cent. The question is whether and how this can be managed to yield more benefits than detriments, while preserving privacy, social convergence, and harmony, while avoiding divergence, repression, and instability through disharmony.

The imperative for conscious regulation Network science tells us that real-world networks share two characteristics. The first is growth with time, and the second is that new nodes link more often to more connected nodes, or hubs. Growth and preferential attachment result in the emergence of a few, highly connected, dominant hubs in all networks, whether the networks are of the cells in our bodies, computer chips, transport networks for airlines, social networks connecting people, or the World Wide Web. These characteristics are common across

networks of any size and are scale-free.

The dominance manifested by companies such as Facebook, Amazon, Netflix, and Google, combined with the attenuated influence of less connected nodes highlights the role of regulation and structure for equitable development and outcomes in networks. The same issues of dominance and the need for regulation arise in democracy. In India, outrageous changes introduced recently with regard to election funding have increased opacity and the potential for abuse at the heart of democratic processes. Political parties can now receive foreign or domestic funding from any source without constraint, and funds can be anonymous through electoral bonds. Introduced with retrospective effect, both the National Democratic Alliance and the Congress benefitted, as previous adverse judgments were nullified. Therefore, one pointer is the need for regulation and appropriate controls applied in a host of areas including news and social media.

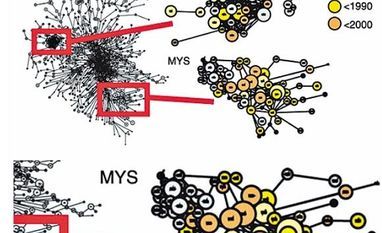

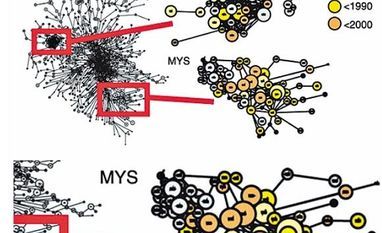

Evidence-based policies An entirely constructive aspect of digitisation relates to the application of network science to issues by mapping the links between factors and actionable policies. Examples are the connection between genes and diseases for effective treatment,1 or the feasibility of upgrading products and exports for countries. An example of how proximate products and exports developed over 20 years is visualised in Chart 1, showing the Revealed Comparative Advantage (RCA) of Colombia (COL) and Malaysia (MYS) in production and exports from 1980 to 2000. The premise is that most upscale products are from a densely connected core, while lower order products are in a less connected periphery. Countries tend to move to products close to those for which they have specialised skills.

The lower chart is for Malaysia alone (it helps to view enlarged images in colour on a screen to trace the progression).

)

)