Almost every year, the media focuses attention on the issue of farmers' suicides, so much so that the news has begun to shape the views. This type of reportage has diverted attention from a larger problem afflicting Indian society and urgently requires to be addressed, especially given the new government's declared focus on urbanisation. That is because farmers' suicides are a small - though no less worrying - part of a larger tragedy.

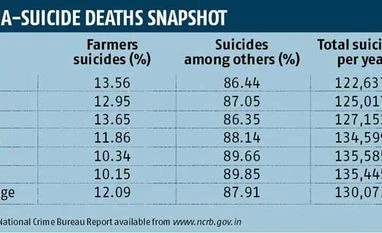

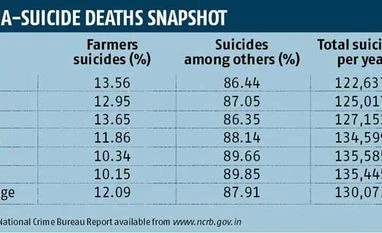

Available statistics on suicides published by Government of India show that urban suicides, i.e. suicides among the non-farming population, outweigh farmers' suicides by over 7:1. Official data reveal that nearly 7,75,000 suicides were recorded in India between 2007 and 2012. Of this, farmers' suicides accounted for 12 per cent and the remaining 88 per cent was unrelated to farming.

Putting suicides in perspective: 70 per cent of India's population live in rural areas, they are mainly into farming and they account for 12 per cent of total suicides, while 30 per cent of the population living in urban areas account for 88 per cent of the suicides. Yet no one talks of the latter. Also, whereas farmers' suicides have steadily decreased from 13.56 per cent to closer to 10 per cent in the past six years, the incidence of urban suicides has increased from 86 to almost 90 per cent.

Let me make it clear here that I am not attempting to belittle farmers' suicides. It is a great tragedy and all efforts to mitigate them are worthy of approval. However, I am attempting to bring to light the real face of suicides in India facilitating a fuller understanding of the problem. The issues of farmers' suicides seem to have been seized by environmental and other social activists groups for their own agenda. Environmental activists have blamed farmers' suicides on modern agriculture that requires use of inputs such as fertilisers, genetically modified seeds, pesticides, and so on. On the other hand, the social activists lay the blame for this tragedy on the government's economic liberalisation policies and globalisation. In this melee of slogans few noticed that in Punjab, by far the agriculturally progressive state in India, there has been hardly any reports of farmer's suicide.

Continuous news about cotton farmers' suicides from Vidarbha region of Maharashtra forced a visit from the then Prime Minister Manmohan Singh a few years ago. Even as rural suicides attract the personal attention of our leaders, I wonder if urban suicides move even municipal corporators.

The single biggest reason for suicides, according to government data, is family problems followed by illness, love affairs, drug abuse, bankruptcy, dowry disputes and poverty.

It is ironic that urban suicides are accepted with equanimity and, therefore, remain ignored and unnoticed. This does not happen in case of other unnatural deaths. For example, 1,39,000 Indians were killed on Indian roads in 2012. This figure is higher than suicides in 2012. While authorities do not attempt to discriminate between rural accidents and urban accidents, why should suicides be regarded differently, with apathy towards urban suicides?

Failing to understand suicide trends in India is one thing, wrongly understanding the trend is quite another.

Let us look at suicides in other countries. Japan is the third largest economy in the world in terms of gross domestic product and India the tenth largest. Paradoxically, Japan has a far higher suicide rate. In Japan, which has just 10 per cent of India's population, the suicide rate is more than double India's. Measured in international terms, 21 out of every 100,000 Japanese people commit suicide in a year. The corresponding figure for India is 11 for every 100,000.

The suicide rates in wealthy countries such as the US, UK , France, Switzerland and so on are all higher than India.

Global suicide rates have been on the increase since 1950. Based on current trends, the World Health Organisation (WHO) estimates that for the year 2020, approximately 1.53 million people will die from suicides. Singapore, which has no agricultural activity to speak of, hit an all-time high in suicides in 2012.

Within India, too, there is considerable variation in rate of suicides (i.e. the number of suicides per one lakh population) among states. In 2012, Puducherry registered the highest rate of suicides with 36.8 followed by Sikkim (29.1). It must be noted that these are agriculturally insignificant states in India. In Punjab, a state known for intensive agriculture, the suicide rate is as low as 3.7, which is way below the national average of 11. Clearly, therefore, the oft-repeated propaganda that adoption of intensive agriculture leads to high farmers suicides is unfounded and unsupported by empirical evidence.

This begs the question: Is suicide linked more to people's attitude than their economic status?

The writer is with Crop Care Federation of India (CCFI) - a registered association of and for the Indian agrochemical industry

)

)