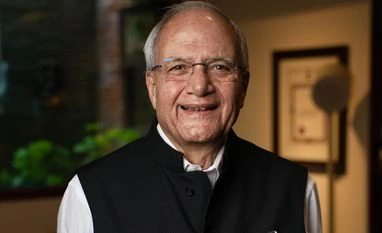

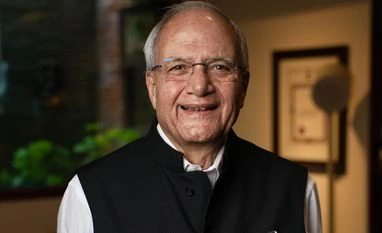

Ajai Chowdhry, co-founder, HCL (Hindustan Computers Limited), and considered the “father of Indian hardware”, believes that India again has an opportunity to foray into the global hardware sector. Chowdhry is also the chairman of EPIC Foundation, a not-for-profit organisation focused on reviving the electronics industry in India, and author of the new book Just Aspire. In an interview with Shivani Shinde in Mumbai, he explains why India can make it in the hardware industry. Edited excerpts:

Would India’s hardware story have been different if HCL and Wipro had continued their focus on the hardware business?

As long as I was in the saddle, the hardware focus continued. This business needs a lot of guts. You are fighting global brands, margins are low and one needs to keep overheads under control. Despite all this, between 2002 and 2008-2009 we were the most sought after company in the country. Wipro gave up much earlier, Zenith also dwindled, because everybody faced the same problem -- margins and fighting the global giants.

We survived for the longest, because we constantly created differentiation in products. When I left HCL, the board suddenly started questioning the new CEO. He wasn’t confident enough to deliver results, and within two years the business was shut down. Wrongly. Just look at the situation today, with all the productivity-linked incentives.

Yes, absolutely, the story would have been different. Everybody, including HCL, got drawn to the high margins of the services business. As a country, we need to move from services to products, and from low value-addition to high value-addition. A decade ago an organisation called iSpirt was created in Bengaluru. They decided to build India as a software product nation. The results are there to see -- the public infrastructure for software is phenomenal. We have to repeat this in other segments and in many other technologies, if we want to leap to higher value-addition.

Almost every country is wooing players to set up fab plants or get into semiconductors. Will India’s attempt at setting up a fab plant be a success?

All over the world, countries want to invest in semiconductors and fabs. It’s very tough to get investments. But in 40 nanometers and above, I believe we still have a chance.

Earlier, when we were looking at policy support for semiconductors, there was this fallacy in our minds that we should have the latest. We wanted the latest technology that would support higher nodes. Higher nodes mean very high expenditure and secondly, the market doesn’t exist. In India there is a market for 28 and 40 nanometers and above. Also, in the past, all incentives from the government were post facto -- first invest, then you get incentives. Nobody will come, because the value is very large.

The proposals that India has received so far were well-qualified, but there was something missing in terms of technology, leadership, or access to markets. Hence, despite Vedanta-Foxconn having everything, their bid was rejected and they need to rebid.

This time the government wants to do things differently. They did not leave it to the bureaucrats. They appointed global Indians from the semiconductor industry as part of the committee to evaluate proposals.

Will the government’s $10-billion incentive work, when the US Chip Act talks of $280 billion in funds?

We have to start. No other country is giving 70 per cent of capex -- 30 per cent is the highest. Our requirements are different. We don’t want 15 plants, while the US wants 15-20 plants. We don’t want the latest nodes. If you want the latest notes, $10 billion is not enough. We should not just look at silicon. We should look at compound semiconductors. It’s a huge market in India. This would need investments of $200-300 million.

I think this time the government is ready to listen. When I started writing about semiconductors 20-odd years ago, no one would listen. We need to be a product nation, we should make our own chips for specific areas and we should make our products. Electronic products have to be designed in India and made in India. If we want semiconductors to be successful, products must be made here.

Do we have a big enough market in India?

Initially, it has to start with the domestic market, but we must become a product country. Nodes of 40 nanometer and above are required for products like washing machines. We need to analyse where we should make our efforts. I have suggested that we pick 100 products to start with, then go to 500 products, and then create an ecosystem. The states also have a part to play. They can focus on creating design capabilities by partnering with research and education institutions.

As an entrepreneur, what is your take on the unicorn phenomenon?

In the last three to five years we have overdone the unicorn bit. How does it matter? These are all valuations of today, tomorrow they will go down. These are not the right markers for us to evaluate the start-up ecosystem. The right mark-up is how many new start-ups are coming up every year, and how many of them are being angel-funded and mentored.

Angels are also becoming very strict in asking for compliances. So, in India Angel Network, which I’m part of, we put in a process whereby every start-up that gets funded by the network has to give a compliance report signed by the head of finance and the CEO, to say that this is accurate. Unless you push this kind of governance on them, start-ups don’t know better.

)

)