The national lockdown due to the spread of the deadly Covid-19 virus — now a month has passed since March 25 — has crushed what was an already faltering Indian economy. The lockdown relaxations since April 20 are related to “movement of cargo, farming, fisheries, plantations, animal husbandry, manufacturing in special economic zones, coal, mineral and oil production and self-employed plumbers, carpenters, motor mechanics and electricians”. This should generate income for some and provide a modicum of relief to corresponding creditors.

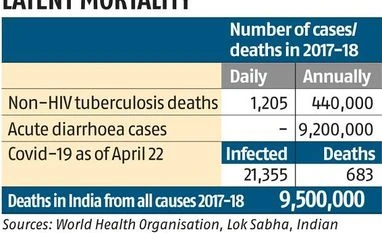

The table lists the numbers of Indians afflicted by two communicable diseases and the Covid virus. By April 22, Covid-19 deaths in India totalled 683. To keep matters in perspective, in 2017-18 about half a million deaths in India were caused by non-HIV tuberculosis and diarrhoea. Perhaps the Covid virus would have caused more deaths without a draconian national lockdown. However, could the central government have administered the lockdown medicine in more specifically targeted doses?

Illustration: Binay Sinha

The ongoing national lockdown, despite the exceptions since April 20, has crippled economic activity resulting in sharply reduced earnings for informal sector workers. It is possible that many in the informal sector may succumb to non-Covid ailments coupled with malnutrition and lack of medical attention when hospitals are perforce focusing on treating Covid patients. In this context, I am reminded of a refrain from a Hindi movie in which Utpal Dutt plays a senior private sector executive. Dutt’s character haughtily rejects the pay rise demands of striking workers. The background chorus, which played through the movie was the workers singing “hum bhook se marne wale kya maut se darne wale” (we who are dying of hunger, would we be afraid of death?).

Prior to the announcement of a national lockdown the government had overlooked its drastic consequences for daily-wage and migrant workers. This is another important lesson for later. Namely, that the government has to ensure painstaking collation of numbers through frequent sample surveys of the living conditions and earnings of daily-wage and migrant workers said to number around 150 million.

Some have raised the spectre of runaway inflation and a balance of payments crisis if central government spending is increased considerably. Reflecting declining global demand, Brent crude oil price is down at $20 a barrel. On April 20, for the first time ever US oil price futures were negative because US oil producers lack storage space. Given the sharp reduction in overall demand in India and elsewhere, inflationary pressures are distant. Clearly, the government can increase spending to raise consumption at the lowest income levels without worrying about inflation. It is the Reserve Bank of India (RBI) which should be careful when exercising regulatory forbearance vis-à-vis creditors to segregate pre-February 2020 insolvencies from those that emerge as a result of the Covid-induced lockdown.

Although the International Monetary Fund (IMF) has projected Indian gross domestic product (GDP) growth at 1.8 per cent for 2020-21, this number may end up at negative 5 per cent or worse. In 2020-21, total domestic tax revenues, net foreign inward investments and remittances will be sharply down. To enable higher public spending, the RBI would eventually need to purchase central government debt directly. And, if the combined deficit of the central and state governments rises to 14 per cent of GDP — so be it. The same number for 2019-20 was almost 9 per cent of GDP. For purposes of comparison, developed countries have announced additional spending of 10 per cent of GDP or more to dig themselves out of the Covid-19 hole.

Even as the central government and the RBI take measured steps to prevent the economy from descending into a tailspin, the urgent needs of daily-wagers, migrant labour and the rural landless should be taken into account. This does not need saying. However, there were confirmed reports of the wealthy being flown back from foreign locations, and middle-class children were ferried from coaching centres in Kota to their homes in Uttar Pradesh. At the same time, the central government has not found it possible to provide trains for all migrant labour who want to return to their villages with a quarantine period of 14 days on reaching their destinations.

)

)