Target 2019: NDA fast-tracks rural homes for 10 million

From the look of it, NDA is focused on PMAY, just like UPA was on MGNREGA

)

premium

Last Updated : Sep 01 2017 | 2:13 AM IST

The government has decided to give its rural housing scheme a big push, which analysts believe could play a role in the 2019 general election verdict.

Conversations with bureaucrats and experts indicate that the Narendra Modi-led NDA government is focused on the Pradhan Mantri Awas Yojana (PMAY) quite like UPA government’s efforts on the Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Act (MGNREGA). In many ways, MGNREGA, the world’s largest state-funded employment scheme promising 100 days of work to rural households, is believed to have helped UPA return to power in 2009.

“A public representative is likely to attend the griha pravesh (house warming ceremony) of each newly constructed house. The idea behind the PMAY — for building 10 million houses — is to create a feel good factor in rural India by giving the people a house and 90 days of work before the 2019 general elections,’’ a senior government official told Business Standard. The importance of PMAY can be gauged from the fact that all state chief ministers were roped in to launch the scheme, he pointed out.

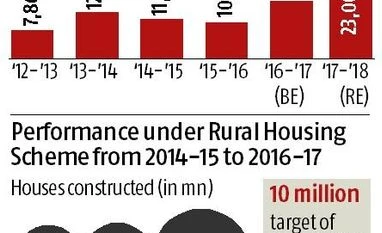

The data show that budgetary support to PMAY, a refurbished version of the erstwhile Indira Aawas Yojana (IAY), has increased by 127% under the NDA government to Rs 23,000 crore in 2017-18, from Rs 10,116 crore a year ago. In comparison, the total expenditure of the central government has risen by 19.8% in the same period. This allocation for PMAY does not include contributions by state governments to the scheme.

The Centre has also sought to expand the scope of PMAY by dovetailing it with various other schemes that are running parallel. In addition to giving a cash amount of Rs 1,20,000 for constructing a house under PMAY, the NDA government is also providing a cooking gas connection under the Ujwala Yojana, a cash payout of Rs 12,000 for building a toilet under Swachh Bharat and 90 days of work under MGNREGA. Besides, it is working on a proposal to electrify homes under the Deen Dayal Upadhyaya Gram Jyoti Yojana (DDUGJY).

“Around 90% of beneficiaries (of PMAY) reside in the states of Assam, West Bengal, Bihar, Jharkhand, Odisha, Uttar Pradesh, Madhya Pradesh, Chhattisgarh, Maharashtra, Rajasthan and Gujarat,” said an official.

Other than West Bengal and Odisha, the remaining states in the list are ruled by the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP).

The gameplan

By the end of March 2019, the government hopes to build 10 million houses. It had initially planned for 4.4 million houses in 2016-17, another 3.3 million in FY18 and the balance in FY19.

The progress was slow last year — since the November launch, only 400 houses were constructed under PMAY in 2016-17, according to government sources. In the current financial year, 2,25,000 houses have been built till date under PMAY. In addition, about 3.2 million houses as part of IAY were completed in 2016-17.

Compare the numbers with the UPA government’s tally. On average, it completed around 1.6 million houses under IAY annually, years after their construction had begun.

Picking up speed

After a slow start, especially due to flood in many states, the government has readjusted the targets. Against the initial target of 7.7 million in the first two years (by the end of March 2018), officials are now looking at completing only 5.1 million. Of the total 10 million, around 4.9 million will be kept for completion in FY19.

While officials expect progress to pick up in the coming months — roughly 4.6 million houses have been sanctioned and construction has begun for around 4.1 million — achieving these targets will be a challenge, despite the government claiming to have cut construction time by two-thirds. To meet the targets, the government will have to surpass the record speed of construction in 2016-17.

The spend

Based on the estimates provided by the government, the cost of building 10 million houses works out to around Rs 1.2 lakh crore. The government provides Rs 120,000 for constructing a house in plain areas and Rs 130,000 in hilly and northeastern states. The construction cost is shared between the Centre and the states in a 60:40 ratio in plain areas and 90:10 in hilly and northeastern states.

The Centre’s cost has been calculated at Rs 81,975 crore over three years, with the balance funded by states. So far, the central government has released Rs 39,000 crore. Another Rs 21,000 crore is expected in the next Budget.

The remaining Rs 21,975 crore will be borrowed from Nabard for which the Ministry of Rural Development will have to pay interest. The principal is likely to be amortised through budgetary allocations after 2022.