There is a perception in the market that public sector banks (PSB) are shying away from extending credit to industry and infrastructure, even as credit to retail sector continues to be buoyant. Let me clarify. There is no denying the fact that credit growth remains sluggish and is still in single digits. However, beyond the smokescreen of public sector bank lending lie some facts that need to be put out in the public domain for a better acknowledgement of the reality.

First, if we are comparing the loan growth of PSBs, we should be forthcoming that such a comparison is not the same as comparing one apple to another. For example, the loan portfolio on which the entire growth edifice is built is different for PSBs and private sector banks. The loan portfolio of private sector banks is biased towards low-risk retail loans (in the range of 40 per cent to 50 per cent share of the total loan portfolio), while for PSBs this is around 22 per cent, if we consider just the country's largest commercial bank.

PSB loans have remained more concentrated towards high-risk categories such as agriculture and allied sectors, small and medium enterprises (SME) and infrastructure sectors (let us call them non-retail). These sectors have higher regulatory risk weights and are more sensitive to business cycles. Hence, any demand lag in the system is immediately reflected in the loan portfolio of PSBs.

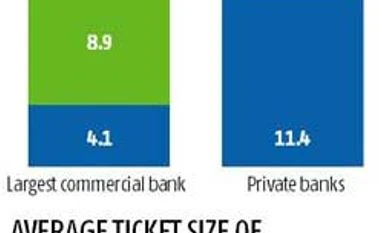

Against this background, we estimated the weighted contribution of retail and non-retail segments in total credit portfolio of select private banks and the country's largest commercial bank. For the sake of convenience, we clubbed together HDFC, Axis and ICICI as private banks. As Figure 1 shows, if we exclude the weighted contribution of retail, the comparable loan growth rates of the banks are nearly identical (in fact, it is 8.9 per cent for country's largest commercial bank, against 8.4 per cent for the combined private banks). Clearly, there is more to the loan growth story than what meets the naked eye.

Second, let us look at the incremental credit of PSBs and other banks. Since the base of PSBs' gross advances is quite big (more than three times) compared to their private bank peers, a 10 per cent credit growth of PSBs is equivalent to 30 per cent credit growth of private banks. For example, FY16 figures show that while the incremental credit of PSBs was at Rs 53.4 lakh crore, for private banks it was only Rs 18.1 lakh crore.

In addition, the credit card business of private sector banks is included in their total advances. That is not the case with PSBs. According to a guesstimate, if we exclude the credit card outstanding portfolio from the private sector banks' outstanding loans, there could be a decline in headline credit growth by around one per cent or so.

Third, let us address the issue that if retail loan book is expanding for PSBs, whether one should draw the conclusion that lack of capital is not the culprit.

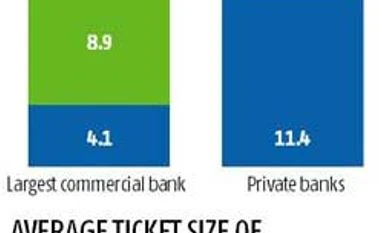

Typically, bank lending to companies, which includes project finance under the specialised lending head, has a significantly higher ticket size. In fact, on an average, the average ticket size for large companies may be as much as Rs 300 crore, for mid-level companies around Rs 25 crore, and for SMEs around Rs 10 crore or so.

In contrast, the average ticket size for home loans is only around Rs 11 lakh. Given these numbers, the capital requirement for an average corporate loan may be thus as much as 115 times compared to a retail loan, after adjusting for risk weights and capital charge. Thus, the capital requirement for the retail sector is indeed peanuts when compared to the corporate loans portfolio.

Additionally, with capital being set aside for provisioning, it also becomes difficult for PSBs to provide fresh lending to big-ticket borrowers. The housing sector - the lending to which has shown growth, has risk weights tied to the LTV ratio and the amount of loan raised - provides a much more secure mode of lending to the banks. Hence, capital is indeed the culprit, if we look at the issue purely from a commercial point of view. In the wake of higher provisioning requirements and the Basel III implementation deadline approaching, PSBs have to take steps to bolster their capital adequacy.

Taking cognisance of all the above factors, it is not entirely correct to say that PSBs are always laggards in terms of credit portfolio expansion. We are not denying that PSBs are impacted by asset quality. In fact, even though PSBs are marred by high non-performing assets (NPA) they are still cognisant about their role and responsibilities in the nation-building exercise. The answer to a logical question of PSBs funding to riskier areas such as infrastructure is that these areas are the largest creators of employment, besides being a priority for the nation. If that is the case, a better way to study efficiency of bank operations is to assess the number of jobs created per unit of loans disbursed and not always their level of NPAs or low credit growth, at least in a developing country like India.

The author is chief economic advisor, State Bank of India. The views are personal.

Tapas Parida and Shambhavi Sharma contributed to this article

)

)