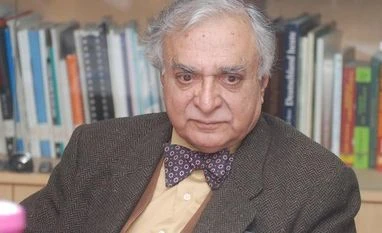

Obituary: Economist and BS Columnist Deepak Lal passes away at 80

Classicism and liberalism were two values that defined the man

)

premium

Deepak Lal was one of the many wonderful economists India exported to the West

Deepak Lal, another of those wonderful Indian economists that India exported to the West, passed away on April 30. He was deeply suspicious of governments and politicians. That could have been one reason why he quit the foreign service in 1966 after just three years. It was an inspired decision. He would never have fitted into the bureaucracy, where brilliance is sneered at.

For five years, from about 2014, whenever he was in India, he and I sat in adjacent chairs at the weekly editorial meetings of this newspaper. He would shuffle in with his walking stick, mask and, in the summer, his straw hat. At first he would bring along his pipe but later on I think he gave up tobacco.

In these five years, I had just one grievance against him. As the designated supplier of samosas, I took around 2,500 samosas to the meeting, at the rate of 10 per meeting over about 250 weeks. He never took one, never, not once. In fairness, though, he didn’t touch the biscuits, either.

He was past his academic prime by then and had also developed fixed views on most things. But this is better than those who develop fixed views in their forties. It wasn’t such a bad thing in his case also because he was rarely wrong. And, above all, he still knew his economic theory. Most Indian economists have either forgotten it or never knew it to begin with.

Born in Lahore in 1940 and educated at the traditional triad of Doon School, St Stephens and Oxford University, he drifted away to the US at the end of the 1980s. Before that, he had taught in England. He eventually became a professor of economics at UCLA.

His research interests were hugely varied and you could find the entire list on his webpage. Not a lot of it was very influential in the mainstream economic thinking, but he did stick to his guns that always had two barrels — classicism and liberalism. These two values defined the man.

For five years, from about 2014, whenever he was in India, he and I sat in adjacent chairs at the weekly editorial meetings of this newspaper. He would shuffle in with his walking stick, mask and, in the summer, his straw hat. At first he would bring along his pipe but later on I think he gave up tobacco.

In these five years, I had just one grievance against him. As the designated supplier of samosas, I took around 2,500 samosas to the meeting, at the rate of 10 per meeting over about 250 weeks. He never took one, never, not once. In fairness, though, he didn’t touch the biscuits, either.

He was past his academic prime by then and had also developed fixed views on most things. But this is better than those who develop fixed views in their forties. It wasn’t such a bad thing in his case also because he was rarely wrong. And, above all, he still knew his economic theory. Most Indian economists have either forgotten it or never knew it to begin with.

Born in Lahore in 1940 and educated at the traditional triad of Doon School, St Stephens and Oxford University, he drifted away to the US at the end of the 1980s. Before that, he had taught in England. He eventually became a professor of economics at UCLA.

His research interests were hugely varied and you could find the entire list on his webpage. Not a lot of it was very influential in the mainstream economic thinking, but he did stick to his guns that always had two barrels — classicism and liberalism. These two values defined the man.

Topics : Deepak Lal