Poetic existence

The movie has Adam Driver as the eponymous character who drives a bus in New Jersey's Paterson

)

premium

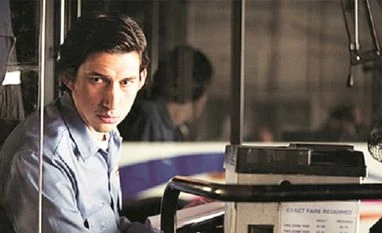

A still from Paterson

Almost 95 per cent of the jobs are regular jobs that one does for paying utilities and raising a family. But what keeps people in these jobs going is that they live a parallel life. This was my biggest takeaway when I watched Jim Jarmusch’s hypnotic Paterson, which I watched at IFFI Goa. The movie has Adam Driver as the eponymous character who drives a bus in New Jersey’s Paterson.

He has a seemingly quotidian life in suburbs with a loving girlfriend (Golshifteh Farahani) and a lovely dog and a post-prandial beer at his neighbourhood bar. But every day he writes poems between work or lunch break on topics as disparate as match boxes and his childhood. The fun chattering among the passengers keeps his creative juices flowing as well. The only music in his working life is the pressurised hiss of the bus doors.

The movie’s most levitating moments are when Paterson’s musings on the page are transposed on the screen. Driver is simply magical in the role of Paterson. It’s hard to imagine anyone else as the pituitive freak who is broad-chested, like a beefier version of Karl Ove Knausgaard, but with a tender heart. The extraordinary warmth that he imbues his character with makes it near impossible to detect the sources of his special access to the human heart. Him as Paterson reminded me, not in a bad way, of 19th century novelist Thomas Love Peacock’s famous quipped about a poet’s mind, “The march of his intellect is like that of a crab, backwards.”

The protagonist seems to have internalised the Amiri Baraka motto: “Art-ing is what makes art.” Despite his girlfriend’s nagging, Paterson has least interest in getting a photocopy of his secret notebook full of his poems until the final act when he’s full of remorse because of his unwilling nature. Thanks to a deus ex machine in the form of a Japanese tourist sharing the bench with him in a park by the Passaic Falls, the movie ends with a distraught Paterson again going back to the blank page.

He has a seemingly quotidian life in suburbs with a loving girlfriend (Golshifteh Farahani) and a lovely dog and a post-prandial beer at his neighbourhood bar. But every day he writes poems between work or lunch break on topics as disparate as match boxes and his childhood. The fun chattering among the passengers keeps his creative juices flowing as well. The only music in his working life is the pressurised hiss of the bus doors.

The movie’s most levitating moments are when Paterson’s musings on the page are transposed on the screen. Driver is simply magical in the role of Paterson. It’s hard to imagine anyone else as the pituitive freak who is broad-chested, like a beefier version of Karl Ove Knausgaard, but with a tender heart. The extraordinary warmth that he imbues his character with makes it near impossible to detect the sources of his special access to the human heart. Him as Paterson reminded me, not in a bad way, of 19th century novelist Thomas Love Peacock’s famous quipped about a poet’s mind, “The march of his intellect is like that of a crab, backwards.”

The protagonist seems to have internalised the Amiri Baraka motto: “Art-ing is what makes art.” Despite his girlfriend’s nagging, Paterson has least interest in getting a photocopy of his secret notebook full of his poems until the final act when he’s full of remorse because of his unwilling nature. Thanks to a deus ex machine in the form of a Japanese tourist sharing the bench with him in a park by the Passaic Falls, the movie ends with a distraught Paterson again going back to the blank page.

A still from Paterson