As US closes borders, Haitian refugees trapped in Mexico lose hope

The suspended order halts general refugee admissions for 120 days

)

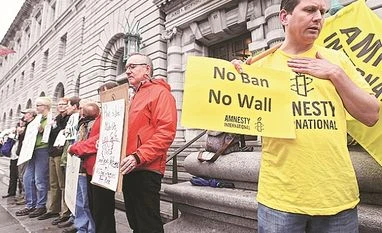

LEGAL VALIDITY Protesters outside the 9th US Circuit Court of Appeals courthouse in San Francisco, after it heard arguments regarding President Donald Trump's temporary travel ban on people from seven Muslim-majority nations Photo: Reuters

A United States federal court has blocked President Donald Trump’s January 27 executive order barring citizens from seven majority Muslim countries from entering the US, but the impacts of the travel ban are already being felt at the nation’s borders.

The suspended order halts general refugee admissions for 120 days and Syrian admissions until further notice and puts a limit of 50,000 admissions per year, down from 150,000. It also imposes major legal hurdles for those processing asylum applications.

Along with the Trump administration’s proposed wall along the US-Mexico border, this situation has dealt a historic blow not just to Muslim immigrants but to the American asylum and refugee system in general – including to the more than 30,000 asylum seekers and migrants now trapped in Tijuana, Mexico, just a few miles from San Diego, California.

A human tragedy in the making

While public attention is distracted with the travel ban’s current legal struggles and the US president’s bombastic anti-Muslim, anti-immigrant rhetoric, refugees have been building up at border crossing points between the US and Mexico, trapped in a legal limbo.

I travelled to migrant shelters in early February to document this developing human rights crisis. I met the kinds of people one would expect: Mexican women escaping cartels and gender-based violence, as well as Guatemalans, Hondurans and Salvadorians fleeing Central America’s unceasing gang violence.

There are also less likely suspects: Haitians who sought refuge in Brazil after the 2010 earthquake in their home country, but who have been forced to move on again due to Brazil’s profound economic and political crisis, which has dramatically reduced job availability. These Haitians aren’t necessarily the typical “economic migrant”; many are engineers, physicians, architects between 20 and 30-years-old.

Indeed, this little-known group makes up the bulk of migrants stuck in Tijuana. According to Tijuana migrant activist Soraya Vázquez from the Comité Estratégico de Ayuda Humanitaria Tijuana, six Haitians arrived in Tijuana on May 23 2016. The next day there were 100. Two months later: 15,000.

By the end of December 2016, nearly two months after Donald Trump’s surprise election, some 30,000 Haitians had gathered there, most by way of Brazil, apparently through a trafficking network that Vázquez says is not yet documented.

For comparison, 10,000 Syrians have applied for asylum in the US in the same period.

Asylum seekers cannot legally work, have no permanent residence, and, if they’re Haitian, often don’t speak Spanish. Yet they must support themselves and their families while they wait for US immigration officials to figure out whether or when their asylum applications can be granted.

They live in Tijuana’s open-air dumps, sewer-system holes and the surroundings of improvised migrant shelters. Many seek all manner of menial jobs on the black market, cleaning houses and offices, working in sweatshops, or delivering pizzas for as little as US$1.30 a day.

Women are frequently offered generic “jobs” in Canada, no description included, along with airfare. All they have to do is give up their passports. The web pages associated with these alleged companies show a permanent error message. These are, not surprisingly, typical trafficking strategies.

Disposibility pockets

When I was there, the whole sad situation on the border recalled what scholar Henry A. Giroux calls the “machinery of disposability”: