Home / Sports / Other Sports News / Nativist politics forces Mesut Ozil out of the German football team

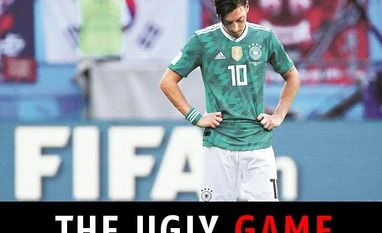

Nativist politics forces Mesut Ozil out of the German football team

Dhruv Munjal on why Germany - and the world - are poorer for it

)

premium

Mesut Ozil

Last Updated : Jul 27 2018 | 9:00 PM IST

It is terribly unfortunate — and equally ironic — that the aftermath of a magnificent World Cup, whose final was illuminated by two sumptuous takes in front of goal by two young Frenchmen of African parentage, is being sullied by a row around multiculturalism. All allegedly provoked by a somewhat ill-judged photograph.

It is almost comical that when Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan posed with the UK’s Queen and her prime minister, Theresa May, in London in May, no feathers were ruffled. Yet, when Mesut Özil, a man unabashedly proud of his Turkish roots, decided to stand alongside the country’s president, it invited a response so vitriolic that the 29-year-old announced earlier this week that he was ready to give up playing for Germany — a country whose gilded, world-thwarting class of 2014 he was such an indispensable part of.

Erdogan is an autocrat in the truest sense of the word: his suppression of press freedom, brazen interference in the judiciary and imposition of internet censorship all point to a leader who is very much a reflection of our right-wing times. But Özil, at least on the face of it, wasn’t there to endorse his politics. “Not meeting the president would have been disrespecting the roots of my ancestors, who I know would be proud of where I am today. For me, it didn’t matter who was president, it mattered that it was the president,” he later said, justifying the meeting.

Özil, who was born in Gelsenkirchen after his grandfather migrated to Germany in the 1970s, hasn’t always had the easiest time dealing with this dual allegiance. In 2010, when he played against Turkey for the first time, in Berlin, he was jeered at by the away fans. A year later, when the two sides were set to meet again, Özil, fearing another torrent of insults, actually considered sitting the game out, a request that was turned down by the German management. Post his departure from the German team, however, the Turks have predictably softened their stand. Authorities in his ancestral town of Devrek have switched the sign marking “Mesut Özil Avenue” from the player’s picture in a Germany shirt to the controversial Erdogan photo op — all because “they watched with sadness what was done to him”.

This sense of convenient nationalism exhibited by Turkey is hardly the problem, though. Özil’s walking out is a sad comment on Germany’s standing, not only as a football powerhouse, but also as a nation in general.

In the run-up to the 1998 World Cup, the racially diverse make-up of the French team was severely criticised by certain rigid sections of French society. In the end, Zinedine Zidane, Lilian Thuram, Youri Djorkaeff and Patrick Vieira superbly showcased that, no matter what was being said beyond the field, the French national team was a paragon of oneness and multiculturalism. And who knows, had it not been for them, the immigrant kids Paul Pogba and Kylian Mbappé may never have aspired to pull on the blue for France. Two Sundays ago, these superstars saw their faces, much like Zidane & Co had 20 years earlier, light up the Arc de Triomphe amid an unmistakable haze of blue, red and white.

You know Germany is in no position to affirm such virtues of integration when Lothar Matthäus, the country’s 1990 World Cup-winning captain, says that “Özil never felt comfortable in the Germany shirt”, or when Reinhard Grindel, a former member of parliament and president of the German FA, feels that “there is too much of an Islamic culture” in German cities, or when Mercedes-Benz, official partners of the national team, drop Özil, undoubtedly a star player, from their official campaigns. Sadly, all of this is indicative of nothing less than a sporting world torn asunder by detestable politics.

And then there is the football. It always comes down to the football. We know what Özil is like on the pitch — a Rolls-Royce footballer with an unmatched eye for the defence-piercing, match-winning pass; a glider of a midfielder who sees stuff the average football brain cannot even fathom, let alone execute. But when he goes missing, he really does go missing, resembling a lost passenger on a train platform. Often in the past, his club Arsenal’s failures in big games have been pinned on him. In the physically demanding world of the Premier League, Özil has been pilloried for his lack of work ethic and defensive discipline. And while a lot of the fault-finding is valid, there is little doubting that Özil’s “luxury player” tag makes him a soft target. Had Germany not suffered a calamitous World Cup, we wouldn’t have been sitting here debating a player’s heritage. We still shouldn’t be, but then when big teams crash out of major tournaments on the back of abject performances, scapegoats are required urgently.

Özil was, in fact, one of the better players for Die Mannschaft in Russia. He created more chances per 90 minutes than any other player in the tournament. Against South Korea, the game that confirmed the defending champions’ exit, Özil was easily the brightest spark. If you were to rely purely on football logic, there were players in that German squad who fared much worse than Özil. A stodgy Sami Khedira, seemingly out of legs in midfield, an over-adventurous Jérôme Boateng routinely caught out of position at the back and a hopelessly out-of-form Thomas Müller, who it seemed, had forgotten how to

score goals.

Interestingly, Khedira is half-Tunisian and Boateng is half-Ghanaian — both have been spared the anti-immigrant vitriol that has come Özil’s way.

The partisan nature of this saga was perhaps best captured by the comments of Bayern Munich President Uli Hoeness, a former World Cup winner himself. “I am glad that this scare is now over. He had been playing sh** for years. He last won a tackle before the 2014 World Cup. And now he and his sh**** performance hide beyond this picture,” he told Sport Bild. Hoeness failed to acknowledge how his own Bayern Munich players — particularly Müller and Mats Hummels — did little to help the team in Russia.

In an increasingly black-and-white world, much like the German team’s colours, Özil, as much as he wants, just cannot have “two hearts, one German and one Turkish”. And amid this strain, international football is the loser.