Busking tradition: One of the most civilised things in the world

I think tradition of busking is one of most civilised things in the world, says the author

)

premium

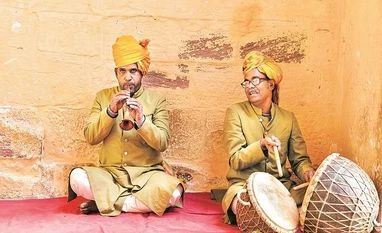

This dignity of the European busker is absent in our parts and this is not the fault of the Indian musician. We have many flaws as a society but one thing we can be justifiably proud of is the quality of our music

I was in Rome earlier this month on work. Actually a few miles outside Rome, on the road to Fiumicino airport, in a hotel surrounded by very little. It was a generic place, with large concrete parking lots and deserted like an American suburb. It was singularly unattractive and so each day I could get away I took the bus into Rome.

Once there, I walked around in desultory fashion to take in the city: the Pantheon, the Colosseum and the arches and, of course, the Palatine hill. Italy is full of young Bangladeshi men, similar looking: thin, dark and short, spirited and full of hustle. The recent arrivals were selling iced water and selfie sticks; the ones more settled in were waiters, chefs and managers of street stalls. It was pleasant to chat with them, in my broken and Maganlal Meghraj-accented Bangla, and to hear their stories and tell them mine. They are everywhere: a couple of years ago my wife and I travelled across Italy, needing to speak nothing other than Bengali.

This time, having walked through much of Rome (it is very small and unchanged over the centuries, which is why it’s called the eternal city) on my first trip into town, I consulted the map to see what to do for trip two. I noticed I hadn’t been to the Spanish Steps, where a church sits on top of an unusually grand stone stairway large enough to seat a thousand people. As I approached it, around 11.30 am, I saw standing in one corner of the square, just off the pavement, a woman singing.

She was a middle-aged soprano and she held herself in formal fashion, with pride. She sang looking up into the middle distance, wearing a velvet gown (it was horridly warm), her bust thrust out, and with make-up on. She was singing something I knew: Charles Gounoud’s “Ave Maria”. She was excellent: unhurried and effortless. A man sat a few feet to her left, playing in accompaniment. His keyboard was amplified through a small portable speaker, but her singing was not.

She sang naturally, projecting out. Her voice cut clean through the air, filling up the square. The open case inviting contributions and support had a few dozen coins, perhaps ^40 or so. I tossed in a coin and listened for a while by the side. When it ended, a few of us applauded and she acknowledged us with smiles and blown kisses.

I think the tradition of busking, which is what street performance of music is called, is one of the most civilised things in the world. The word busker means an itinerant entertainer. What struck me when I first saw one, on my first visit to the United States 30 years ago, was how high the quality of the musicianship was. I was playing with a band in those years and so I knew a thing or two about music. What I was hearing was far ahead of anything I had heard live from young musicians before.

Once there, I walked around in desultory fashion to take in the city: the Pantheon, the Colosseum and the arches and, of course, the Palatine hill. Italy is full of young Bangladeshi men, similar looking: thin, dark and short, spirited and full of hustle. The recent arrivals were selling iced water and selfie sticks; the ones more settled in were waiters, chefs and managers of street stalls. It was pleasant to chat with them, in my broken and Maganlal Meghraj-accented Bangla, and to hear their stories and tell them mine. They are everywhere: a couple of years ago my wife and I travelled across Italy, needing to speak nothing other than Bengali.

This time, having walked through much of Rome (it is very small and unchanged over the centuries, which is why it’s called the eternal city) on my first trip into town, I consulted the map to see what to do for trip two. I noticed I hadn’t been to the Spanish Steps, where a church sits on top of an unusually grand stone stairway large enough to seat a thousand people. As I approached it, around 11.30 am, I saw standing in one corner of the square, just off the pavement, a woman singing.

She was a middle-aged soprano and she held herself in formal fashion, with pride. She sang looking up into the middle distance, wearing a velvet gown (it was horridly warm), her bust thrust out, and with make-up on. She was singing something I knew: Charles Gounoud’s “Ave Maria”. She was excellent: unhurried and effortless. A man sat a few feet to her left, playing in accompaniment. His keyboard was amplified through a small portable speaker, but her singing was not.

She sang naturally, projecting out. Her voice cut clean through the air, filling up the square. The open case inviting contributions and support had a few dozen coins, perhaps ^40 or so. I tossed in a coin and listened for a while by the side. When it ended, a few of us applauded and she acknowledged us with smiles and blown kisses.

I think the tradition of busking, which is what street performance of music is called, is one of the most civilised things in the world. The word busker means an itinerant entertainer. What struck me when I first saw one, on my first visit to the United States 30 years ago, was how high the quality of the musicianship was. I was playing with a band in those years and so I knew a thing or two about music. What I was hearing was far ahead of anything I had heard live from young musicians before.

This dignity of the European busker is absent in our parts and this is not the fault of the Indian musician. We have many flaws as a society but one thing we can be justifiably proud of is the quality of our music