When writing a book leaves a (literal) mark on its author

Yet the wages of a book go deeper than royalties or celebration

)

premium

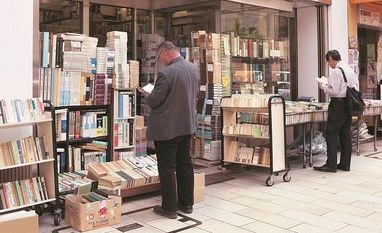

Two dozen Japanese firms have set up at least 62 shops or distributorships selling secondhand Japanese goods in eight South-east Asian countries. Photo: iSTOCK

It is a truth too seldom acknowledged that books mark their authors for life. Authors, of course, mark the completion of their books: a party, a bauble, for the lucky few, a check. Yet the wages of a book go deeper than royalties or celebration. So it was that on a Saturday morning last year, just shy of my 54th birthday, I found myself at a trendy tattoo parlour on the Lower East Side, waiting for my artist to arrive. The plan: She would ink onto my forearm a detail from a painting by the Boston-born artist John Singleton Copley, whose biography I had recently written. I spent the better part of a decade in the close company of that fascinating, vexing man, dead some 200 years yet far more alive to me than most of my neighbours. Now he and I were both moving on. A remembrance seemed in order. “A life should leave/deep tracks,” as the poet Kay Ryan writes.