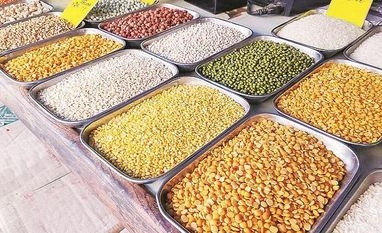

Pricey Indian pulses make open-export policy unfruitful in global market

Experts say difficult to meet both ends - farmers' welfare and promoting agricultural trade

)

premium

Exports of Indian pulses are not growing despite a decade-old ban that was revoked in two steps last year. The reason, industry observers say, is the uncompetitive price of Indian pulses in the global market.

The unit price of exported pulses—mostly chickpeas better known as chole—has consistently risen from $0.84 per kg in 2013-14 to $1.43 per kg in 2017-18, the highest in the last five years.

The quantity exported has dwindled from 346,000 million tonnes (mt) in 2013-14 to 109,000 mt in 2017-18 (till January). In value terms, exports show a declining trend from worth more than $200 million from 2012-13 till 2016-17 to worth $150 million shipped till January in 2017-18, despite the relaxation.

Exports of tur dal (split pigeon pea), moong dal (split green gram) and urad dal (split black gram) were opened in September 2017, earlier than the complete relaxation in December. Even exports of these have not materialised, which does not augur well for the realisation of the recently released draft of the agricultural exports policy, which intends to double India’s farm exports by 2022.

At the other end, pulses farmers who are demanding remunerative prices—through government procurement or in the market—would face losses if Indian pulses have to become competitive in the global market, since that would require lowering of prices realised by farmers.

The unit price of exported pulses—mostly chickpeas better known as chole—has consistently risen from $0.84 per kg in 2013-14 to $1.43 per kg in 2017-18, the highest in the last five years.

The quantity exported has dwindled from 346,000 million tonnes (mt) in 2013-14 to 109,000 mt in 2017-18 (till January). In value terms, exports show a declining trend from worth more than $200 million from 2012-13 till 2016-17 to worth $150 million shipped till January in 2017-18, despite the relaxation.

Exports of tur dal (split pigeon pea), moong dal (split green gram) and urad dal (split black gram) were opened in September 2017, earlier than the complete relaxation in December. Even exports of these have not materialised, which does not augur well for the realisation of the recently released draft of the agricultural exports policy, which intends to double India’s farm exports by 2022.

At the other end, pulses farmers who are demanding remunerative prices—through government procurement or in the market—would face losses if Indian pulses have to become competitive in the global market, since that would require lowering of prices realised by farmers.

commodities graph