Home / Elections / Lok Sabha Election / News / Internal security: Has India become safer in the five years of BJP govt?

Internal security: Has India become safer in the five years of BJP govt?

While terrorism remains a threat to a degree, joblessness poses another big challenge to internal security

)

premium

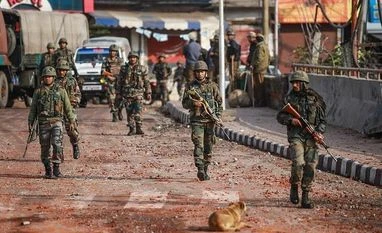

File photo: Army personnel patrol a street during a curfew, imposed after clashes between two communities over the protest against the Pulwama terror attack, in Jammu, Saturday, Feb. 16, 2019.

13 min read Last Updated : Apr 08 2019 | 10:50 AM IST

The Bharatiya Janata Party’s (BJP’s) manifesto for the 2014 election, which began its section on national security by calling for “a review and overhauling of the current system”, defined security in the broadest terms. “Comprehensive national security is not just about borders, but in its broad terms includes military security; economic security; cyber security; energy, food and water and health security; and social cohesion and harmony…”, said the manifesto.

With the National Democratic Alliance (NDA) government approaching the end of its five-year term in office, it is time to audit how successful it has been in overhauling the system. Leaving aside external security and the challenges posed by China and Pakistan, we examine whether India is internally more secure, and if so to what extent, compared to five years ago.

Jammu & Kashmir

The Valentine’s Day car bomb attack in Pulwama, Jammu & Kashmir (J&K) that killed over 40 Central Reserve Police Force (CRPF) troopers, and the consequent decision to disallow civilian traffic when military convoys are plying on main roads in Kashmir, suggests a deteriorating security situation.

On the one hand, the government points to the steady rise in the number of militants “neutralised” (the antiseptic terminology for killed). Compared to 114 militants killed in 2014, it has risen year-on-year to 276 killed last year.

However, that has not curbed militancy. This period has also seen a steady rise in the frequency of militant incidents, and in the numbers of civilians and security men killed. While 28 civilians lost their lives in 2014, that number trebled to 86 last year. The deaths of security men also more than doubled from 46 in 2014 to 95 last year. This year is set to be worse, given the Pulwama debacle and stepped up operations that have followed it.

Yet this troubling body count fails to capture the most worrying dynamic of this period, which is the near-total alienation of the Kashmiri populace, particularly the youth. Across Kashmir, there is the resentful perception that Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s government, along with the broader Sangh Parivar, has driven a consistently anti-Muslim agenda. Kashmiris seethe at militant gau raksha (cow protection), initiatives like ghar wapasi (re-conversion to Hinduism), regulations preventing Muslims from praying in public spaces, and the “love Jihad” bogey – which propagates the narrative of Muslim men feigning love to Hindu women to convert them to Islam.

There is also acute awareness in the Valley of the discrimination faced by Kashmiri youth who seek work outside the state, such as difficulty in renting houses and even targeted violence after incidents such as the Pulwama bombing. Such narratives reinforce the lack of economic opportunity for youth in the Valley and the absence of political engagement, causing estranged youngsters to pick up the gun.

With little training or survival skills, these local militants quickly get killed, usually within six-to-twelve months of joining. When they are cornered, locals who know them come out and pelt stones at the security forces. The soldiers’ inevitable retaliation kills civilians and the consequent funerals – of both militants and civilians – seethe with emotion, motivating even more youths to join the militancy. This vicious cycle means that, even as large numbers of militants are killed, more and more replenish the ranks.

There were hopes of greater engagement with Delhi after the 2014 J&K state election, when the People’s Democratic Party and the BJP formed a coalition government with an “Agenda for Alliance” that promised to “facilitate and help initiate a sustained and meaningful dialogue with all internal stakeholders, which will include all political groups irrespective of their ideological views and predilections.” This political dialogue, which would have acted as a safety valve, never even began.

After India retaliated to the Pulwama car bomb attack with air strikes on a terrorist training camp in Balakot, Pakistan, many fear that the already grim situation could deteriorate as jihadi groups seek to demonstrate their relevance. Ajai Sahni of the Institute for Conflict Management, writes: “The [car bomb] explosion at Awantipora is likely to be a prelude to a tremendous escalation of violence in J&K; to increasing and increasingly visible involvement of Pakistani groups and cadres; and to a progressive transfer of tactics and strategies from Afghanistan to India.”

Internal violence statistics (J&K violence)

Internal violence statistics (J&K violence)

| Year | Civilians killed | Security Forces killed | Militants killed | Total deaths |

| 2014 | 28 | 46 | 114 | 188 |

| 2015 | 19 | 43 | 116 | 178 |

| 2016 | 14 | 88 | 165 | 267 |

| 2017 | 53 | 83 | 218 | 354 |

| 2018 | 86 | 95 | 276 | 457 |

| 2019* | 12 | 57 | 65 | 134 |

| Total | 212 | 412 | 954 | 1578 |

All figures from South Asia Terrorism Portal (SATP)

* 2019 data till April 5

* 2019 data till April 5

Punjab

The killing of three Nirankaris in a grenade blast near Amritsar on November 19, 2018, recalled memories of the decade and a half of terrorism in Punjab, which, coincidentally, was also triggered in 1978 with anti-Nirankari violence by the Damdami Taksal, led by Jarnail Singh Bhindranwale. While that died down in 1993, a rump of the Khalistan movement has survived and Punjab watchers accuse Pakistan’s Inter-Services Intelligence (ISI) of nurturing it, in the hope their time comes again.

After seven persons were killed and 40 injured in a bomb blast in Ludhiana in October 2007, Khalistani terrorists remained dormant for the next eight years. According to the well-respected South Asia Terrorism Portal (SATP), they were unable to inflict even a single fatality in Punjab between 2008-2015. However, in the three years since then, there have been 17 violent strikes, with the consequent arrest of 82 Khalistani suspects.

There is also growing concern about money being fuelled to the Khalistanis from the Sikh diaspora. In a tense meeting last February between Punjab Chief Minister Amarinder Singh and visiting Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau, Amarinder flagged the activities of Khalistanis in Canada and their funding of radicals in India. Trudeau was handed a list of “Category A” Khalistani operatives in that country.

Indian intelligence agencies are now worrying about Pakistan’s offer to open for Sikh pilgrims the so-called Kartarpur Sahib corridor to the Nankana Sahib gurudwara inside Pakistan, for which the foundation stone was laid in November. The agencies see this as a trap that would allow Pakistan-based Khalistani activists an opportunity to subvert and radicalise Sikh youngsters who travel to Nankana Sahib, thus reviving the Punjab insurgency.

North-eastern states

Violence statistics indicate that militancy has abated over the last five years across the eight northeastern states. While 471 militants, security men and civilians were killed in 2014, that figure fell to 72 last year. Nevertheless, security remains elusive with a plethora of armed groups engaged in extortion, abduction and protection rackets. SATP cites former National Security Guard and Assam Police chief, JN Choudhury, as stating: “In (the) northeast, militancy has become almost a cottage industry where extortion and abduction for ransom is seen as an easy means for money.”

In Assam alone, police records show thousands of cases of abduction and extortion. It is common knowledge that armed militant that once fought the Indian government now run lucrative kidnapping and protection rackets. Splinter factions of the National Socialist Council of Nagaland (NSCN) collect “taxes”, and there is extortion by the United Liberation Front of Asom (ULFA), which is now confined to the areas bordering Naga-inhabited areas in Arunachal Pradesh and Nagaland.

Even Manipur, the sole surviving insurgency hotbed, is now more quiet. However ethnic violence dogs the state, especially between Naga and Kuki groups. Another driver of insecurity is the dominant Meitei community’s concern that the Naga-inhabited hill areas of the state could be merged into “Greater Nagaland” as part of a Naga settlement.

At the broader level, the north-east is witnessing growing disenchantment with insurgency and separatism, especially as more and more north-eastern people make their way to big towns and cities and find employment in service industries. As one senior military officer stated about Naga insurgents who came over-ground after the NSCN ceasefire, “Those fighters have exchanged the gun for the guitar and the mobile phone. Now they don’t want to ever go back into the jungle.”

Even so, the central government’s failure to develop a larger political and social narrative to integrate the region with the Indian mainstream ensures that the peace is both sullen and impermanent.

Internal violence statistics (North-east violence)

All figures from South Asia Terrorism Portal (SATP)

* 2019 data till April 5

Internal violence statistics (North-east violence)

| Year | Civilians killed | Security Forces killed | Militants killed | Total deaths |

| 2014 | 245 | 22 | 204 | 471 |

| 2015 | 63 | 52 | 163 | 278 |

| 2016 | 62 | 20 | 85 | 167 |

| 2017 | 35 | 13 | 58 | 106 |

| 2018 | 19 | 15 | 38 | 72 |

| 2019* | 2 | -- | 1 | 3 |

| Total | 426 | 122 | 549 | 1097 |

* 2019 data till April 5

Naxals/Maoists

Given the difficulty being faced by left wing Naxalism (or, interchangeably, Maoism) to survive, even against the inadequate and incoherent response that Indian governments have mustered so far, it would appear that the strategists and political leaders who had once termed it “India’s greatest threat” overstated the case. Overall violence levels have remained broadly static since 2014, with one crucial difference: more Naxals are being killed now and fewer security personnel. Worryingly, about a hundred civilians continue losing their lives to Naxal violence each year.

Meanwhile, Naxal sway is diminishing. In March 2017, Home Minister Rajnath Singh told Parliament that districts affected by Naxalism had fallen from 106 to just 68. A year later, reviewing a police parade, he said “I can say that the LWE (left wing extremism) problem in the country has entered its last leg.”

While the Maoists retain their ability, especially in Chhattisgarh, to sporadically pull off occasional attacks that spectacularly account for most security force casualties, the Maoists are losing ground in most places. SATP assesses: “What was once envisaged as a ‘tactical retreat’ has transformed into sustained strategic reverses.”

Yet, the inequalities and deficit of governance that Naxalism is founded on persists across Jharkhand, Bihar, Andhra Pradesh, Chhattisgarh, Odisha and Maharashtra. This perennially carries the danger of a revival. Furthermore the state as well as central governments are failing to counter the ideas and ideologies that underpin Naxalism.

“The Maoists are certainly in retreat, but the threat is still alive. Sadly, the state appears to lack the sense of urgency required to build the capacities to sustain and consolidate the gains of recent years,” says Deepak Kumar Nayak of the Institute for Conflict Management.

Meanwhile, the Bureau of Police Records and Data highlights a worrying deficit across the country in grassroots law and order structures, which are also the source of the most reliable intelligence. As on January 1, 2017, state police forces were short of a total of 538,237 policemen. The Central Armed Police Forces (CAPFs), in the vanguard of the fight against Naxals has 110,081 posts vacant against a sanctioned strength of 1,154,393.

Internal violence statistics (Naxal violence)

Internal violence statistics (Naxal violence)

| Year | Civilians killed | Security Forces killed | Militants killed | Total deaths |

| 2014 | 127 | 97 | 121 | 345 |

| 2015 | 90 | 56 | 110 | 256 |

| 2016 | 122 | 60 | 251 | 433 |

| 2017 | 109 | 76 | 150 | 335 |

| 2018 | 108 | 73 | 231 | 412 |

| 2019 | 20 | 2 | 50 | 72 |

| Total | 576 | 364 | 913 | 1853 |

All figures from South Asia Terrorism Portal (SATP)

* 2019 data till April 5

Radical Islamism: Daesh

* 2019 data till April 5

Radical Islamism: Daesh

Western intelligence agencies marvel at how few Indian Muslims have been recruited by the Islamic State in Iraq and Syria (ISIS, or Daesh), with larger absolute numbers coming from tiny countries like Maldives and Belgium. SATP’s database registers the arrest of just 164 Daesh sympathizers and recruits in India, with another 69 individuals having been detained, counseled and released till January 23, 2019.

Another 98 Indians actually joined Daesh in Syria, Iraq and Afghanistan, of whom 32 were killed fighting there.

SATP’s Sahni states: “India's response - both at Central and State levels - to the threat of Daesh terrorism has been extremely, one may add, uncharacteristically, proactive, and intelligence and enforcement successes have been exceptional.”

An example of this was the arrest on January 21 of nine members of the self-styled Ummat-e-Mohammadiya by the Maharashtra police. Interrogation revealed they were contemplating attacks, not with bombs, but through unconventional methods such as poisoning food and water sources at major religious gatherings.

However, Sahni warns that, if existing intelligence and enforcement deficits persist, “it is inevitable that one of these emerging groups of Islamist terrorists will 'get lucky', with potentially dangerous - and possibly catastrophic - consequences.”

Other threats

India’s top intelligence and security planners claim to have most security threats covered, but privately admit to disquiet over two emerging threats: Hindu terrorist groups; and a law and order threat stemming from millions of unemployed youth.

Since the Samjhauta Express, Ajmer Sharif Dargah and Mecca Masjid blasts in 2007 and the Malegaon blast in 2008, the Intelligence Bureau (IB) has kept a wary eye focused on what it calls “majoritarian terrorism”, even though Home Minister Rajnath Singht and BJP leaders like Balbir Punj have dismissed the notion of “Saffron terror” as nonsense. “If Hindu groups feel encouraged to adopt terror tactics, we will enter a same spiral from which it will be difficult to emerge”, says a top IB officer, speaking anonymously

There is deep disquiet in the IB at the failure of the National Investigation Agency, which handles terrorism cases, to successfully prosecute four men accused of involvement in the 2007 bombing of the Samjhauta Express, a train that was carrying mainly Pakistani pilgrims, or which 68 were killed. On March 20, a special court acquitted the key accused, Swami Aseemanand and three associates. Aseemanand had been earlier acquitted in the Ajmer Sharif and Mecca Masjid bombings.

Security planners also express grave concern over violence stemming from concerns about employment, particularly violent community agitations demanding reservations in education and jobs. In recent years, communities such as the Patels, Marathas, Jats, Gujjars and the Kapus – who stunned law enforcement agencies by burning a train, three police stations and 80 vehicles in six hours – have staged violent agitations.

One security planner calculates that about 94 per cent of employment is in the unorganised sector, with only six per cent in the organised sector. When the economy is growing rapidly, the labour force gets fully absorbed into the work force. But slower growth hits the unorganised sector hardest.

“Employment creation wins elections. When there was 8 per cent growth in 2008-09, jobs were easy to get and the Congress-led government consequently roared back to power. Without sufficient growth and employment creation, political parties resort to religious polarisation, which creates law and order crises. So employment becomes a key security factor,” explains a senior intelligence officer.

This direct link between employment and security also sees a threat in jobless growth, with traditional jobs being eliminated by growing mechanisation, robotisation and artificial intelligence. They view emerging technologies, such as driverless cars, as a potential threat to the employment of 12 million drivers in India. This is true also of mechanisation in road construction, which generates tens of millions of jobs across India.

Intelligence economists point out it would be hard to compete in manufacturing with China, given its cheap labour, physical infrastructure and ease of doing business. “Our only hope remains the services sector, but government policies must be shaped to facilitate that”, says one officer.

Twitter: @ajaishukla