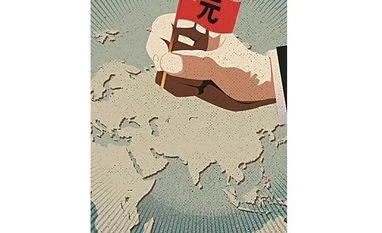

Belt and Road Initiative: 'China's social governance of the world'

For the Chinese, the landmark project is more than just a giant infrastructure project

)

premium

Belt and Road Initiative

China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), articulated by President Xi Jinping in 2013, is recognised as the largest infrastructure and investment project in global history. Spanning 68 countries, including 65 per cent of the world’s population and 40 per cent of global GDP, it is popularly considered an ambitious blueprint for Chinese global hegemony. The BRI’s lumpy progress, however, has also provoked predictions of its imminent demise. Talk to senior members of the Chinese establishment and they’re equivocal about the first point and flatly contradict the second.

As of November 2019, Hu Biliang, dean of the Belt and Road Institute at Beijing Normal University, estimates that China will pour in $10 trillion of funds into the projects in the next decade. By comparison, the 11 multilateral institutions have a combined purse of less than $2 trillion ($1,723 billion) for the same period. Hu says the Chinese government has already spent $40 billion for BRI-related projects.

Yet BRI is much more than rushing through a bunch of infrastructure projects, says Zhang Weiwei, professor of international relations at Fudan University, Beijing. It is more about “setting a sense of priorities. You set the compass first and then build a road”. Zhang has been by turns a visiting professor at the Graduate Institute of International and Development Studies, and at the Geneva School of Diplomacy and International Relations. His CV includes assignments as speech writer for Deng Xiaoping and now Xi, which means unparalleled access to the minds of the men who have shaped China’s policy. He surprised Francis Fukuyama during a debate on the Arab Spring a decade ago, saying it would soon turn into an Arab Winter. He now says Great Britain post-Brexit is on its way to becoming a Little Britain.

According to him, the Chinese concept is to build new points of growth that would “shape up as an irresistible force”. The West has understood BRI as a game of chess among competing nations for economic supremacy. It is not so, he insists. It is like Weiqi, a Chinese strategy board game — which, incidentally, aims to surround more territory than opponents but where the loser also shares the spoils.

As of November 2019, Hu Biliang, dean of the Belt and Road Institute at Beijing Normal University, estimates that China will pour in $10 trillion of funds into the projects in the next decade. By comparison, the 11 multilateral institutions have a combined purse of less than $2 trillion ($1,723 billion) for the same period. Hu says the Chinese government has already spent $40 billion for BRI-related projects.

Yet BRI is much more than rushing through a bunch of infrastructure projects, says Zhang Weiwei, professor of international relations at Fudan University, Beijing. It is more about “setting a sense of priorities. You set the compass first and then build a road”. Zhang has been by turns a visiting professor at the Graduate Institute of International and Development Studies, and at the Geneva School of Diplomacy and International Relations. His CV includes assignments as speech writer for Deng Xiaoping and now Xi, which means unparalleled access to the minds of the men who have shaped China’s policy. He surprised Francis Fukuyama during a debate on the Arab Spring a decade ago, saying it would soon turn into an Arab Winter. He now says Great Britain post-Brexit is on its way to becoming a Little Britain.

According to him, the Chinese concept is to build new points of growth that would “shape up as an irresistible force”. The West has understood BRI as a game of chess among competing nations for economic supremacy. It is not so, he insists. It is like Weiqi, a Chinese strategy board game — which, incidentally, aims to surround more territory than opponents but where the loser also shares the spoils.