Nearly 40 yrs later, Iran's clerics are facing a religious backlash

Critics say that decisions based on a rational assessment of the circumstances should not be tagged as "Islamic"

)

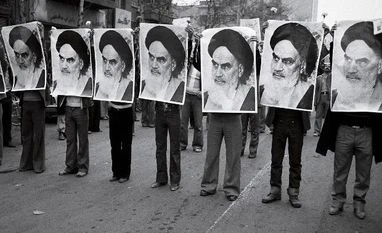

Wikimedia Commons

With Iran’s ruling clergy already preparing to celebrate the 40th anniversary of the 1979 Islamic Revolution, it may be too late to question whether or not the revolution was in fact Islamic. What we can do, at least, is explore the revolution’s degree of Islamicness.

In Iran, like elsewhere in the world, often competing utopian political visions shaped the political landscape of the previous century. Marxism, nationalism and liberalism all played important roles in the 1979 revolution. Yet it was later branded “Islamic” with such insistence that this eventually became its sole adjective.

Most Iranians were religious, which positioned the clergy far ahead of any other political group in being able to mobilise the masses. The clergy benefited enormously from their highly effective religious network, which was both far reaching and fully under their control. By that time, the Pahlavi regime had severely weakened the organising capacities of Iran’s other political groups.

The consolidation of power

After claiming a dominant post-revolution position, the clergy under then-Supreme Leader Ayatollah Khomeini exploited their irreproachable reputation and religious bond with the masses to eliminate their rivals and consolidate their power. They converted Iran’s religious networks into permanent political platforms.

Mosques and other religious spaces and occasions were at the forefront of their propaganda machinery. Mosques were also – and still are – used as polling stations during elections.

The ruling clergy coupled the term “Islamic” with the revolution, calling it a “regime of truth”, to use Foucault’s terminology. More importantly, they impeded the emergence of a non-religious alternative to their peculiar political system. Over the past 39 years, no secular political group has been able to mount a formidable challenge to the Islamic Republic.

Instead, other religious forces have challenged the ruling clergy. They have done so both on the level of practical politics and by way of introducing viable alternatives to the ideal of the Islamic state.

The impetus for Iran’s most significant periods of political unrest in recent decades can be traced to the Islamic reformists. Examples include the reformist movement from 1997 until 2005, and the Green Movement, which emerged after the disputed 2009 elections.

The Green Movement brought the regime to the brink of collapse, and its religious ties were undeniable. Its leaders, Mir Hussin Mousavi and Mehdi Karubi – who are still under house arrest – are both religious figures who have always aligned with the Islamists. The colour green is a religious symbol, hence the name of the movement. A new politico-religious discourse is emerging that offers a viable alternative to the Islamic Republic. The Green Movement must still be understood within the broader “Islamist” school of thought, as it promotes a political role for religion. It is, however, unique in that it envisions this role as part of a democratic polity.

Islam lacks a blueprint for government

The reformist movement amounts to a direct backlash against the ideal of the Islamic state. It targets the foundational pillars of the Shiʿi model of the state, which is based upon Khomeini’s doctrine of wilāyat-i faqīh.

The reformists intend to strip away the ruling clergy’s proclaimed religious legitimacy. They maintain that Islam does not specify a blueprint for political matters and explicitly avoids providing economic, political, or policy prescriptions. The Qurʾān and many Ḥadīths support the notion that humans have the capacity to determine appropriate solutions for their worldly problems. Thus, reformists argue that Islam should be actualised in politics through the political contributions of believers rather than the political leadership of the clergy.

Islam does not stipulate a model political system. This makes it impossible to extract the notion of democratic government from Islamic teachings.

However, one could argue that democracy is an appropriate political system for the Muslim world, based on human reasoning. For example, Mohsen Kadivar asserts: