Water governance reform

The fifth and last in a series of weekly articles on the new National Water Policy

)

premium

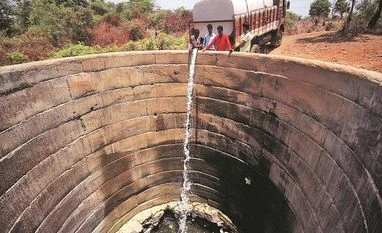

The decision to form the Ministry of Jal Shakti in 2019 was an important milestone in reforming water governance in India. It brought together under one umbrella the departments dealing with drinking water and irrigation. Ever since Independence, the governance of water has suffered from at least three kinds of “hydro-schizophrenia”: that between irrigation and drinking water, surface and groundwater, as also water and wastewater. The new National Water Policy (NWP) suggests urgent action to overcome each of these divisions.

Government departments at the Centre and states have generally dealt with just one side of these binaries, working in silos, without co-ordination with the other side. As a result, critical inter-connections in the water cycle have been ignored, seriously aggravating water problems. We fail to see the link between rivers drying up and over-extraction of groundwater, which reduces the base-flows needed by rivers to have water even after the monsoon.

Placing drinking water and irrigation in silos has meant that aquifers providing assured sources of drinking water dry up over time, because the same aquifers are used for irrigation, which consumes much higher volumes of water.

This has adversely impacted availability of safe drinking water in many areas. And when water and wastewater are separated in planning, the result generally is a fall in water quality, as wastewater ends up polluting supplies of water.

The Central Water Commission (CWC) set up in 1945 is India’s apex body dealing with surface water and the Central Ground Water Board (CGWB) set up in 1970 is the one handling groundwater. Over several decades, even as ground realities and understanding of water have both undergone a sea change, the CWC and CGWB have remained virtually unreformed, working in pristine isolation from each other, with little dialogue or co-ordination between them.

The same pattern is visible in the corresponding bodies at the state level. Ironically, even as groundwater use has grown in significance, becoming India’s single most important water resource today, groundwater departments have only gotten progressively weaker over time.

The NWP suggests merger of the CWC and CGWB to form a multi-disciplinary, multi-stakeholder National Water Commission (NWC). The policy visualises that this exercise at the Centre would become an exemplar for all states to follow.

Government departments at the Centre and states have generally dealt with just one side of these binaries, working in silos, without co-ordination with the other side. As a result, critical inter-connections in the water cycle have been ignored, seriously aggravating water problems. We fail to see the link between rivers drying up and over-extraction of groundwater, which reduces the base-flows needed by rivers to have water even after the monsoon.

Placing drinking water and irrigation in silos has meant that aquifers providing assured sources of drinking water dry up over time, because the same aquifers are used for irrigation, which consumes much higher volumes of water.

This has adversely impacted availability of safe drinking water in many areas. And when water and wastewater are separated in planning, the result generally is a fall in water quality, as wastewater ends up polluting supplies of water.

The Central Water Commission (CWC) set up in 1945 is India’s apex body dealing with surface water and the Central Ground Water Board (CGWB) set up in 1970 is the one handling groundwater. Over several decades, even as ground realities and understanding of water have both undergone a sea change, the CWC and CGWB have remained virtually unreformed, working in pristine isolation from each other, with little dialogue or co-ordination between them.

The same pattern is visible in the corresponding bodies at the state level. Ironically, even as groundwater use has grown in significance, becoming India’s single most important water resource today, groundwater departments have only gotten progressively weaker over time.

The NWP suggests merger of the CWC and CGWB to form a multi-disciplinary, multi-stakeholder National Water Commission (NWC). The policy visualises that this exercise at the Centre would become an exemplar for all states to follow.

Disclaimer: These are personal views of the writer. They do not necessarily reflect the opinion of www.business-standard.com or the Business Standard newspaper