Common Budget leaves railways in a bind

With freight and passenger traffic dwindling, the transition could not have come at a worse time

)

premium

The transition for the Indian railways from having a separate Budget for itself to becoming a part of the Union Budget could not have come at a more inopportune time. This is for several reasons.

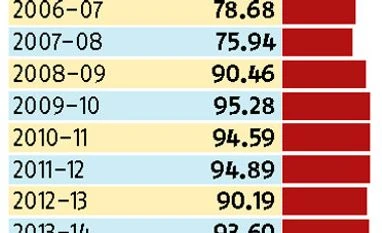

One, the railways are in extremely poor financial health. The operating ratio (gross operating expenses to gross earnings) is expected to touch a low of 94.9 per cent in the current financial year. Even if this revised estimate figure holds, which it may not, it means that virtually all that the railways earn is gobbled up by meeting its running expenses, thus leaving precious little for investment from its own resources. Expenses have shot up because of the government’s decision to implement the Seventh Pay Commission’s recommendations during the current financial year.

While a pay commission is set up around once in a decade and thus contributes to only a periodic spurt in expenses (after that there is a plateauing out at a higher level), earnings should follow a steady upward trajectory. It is here that the situation is most disturbing. For the first time in its history, the railways are set to end the year (2016-17) with freight loadings not just missing the target set for the year but actually going down to 1,093 million tonnes form the 1,101 million tonnes achieved in the previous year (2015-16). This has obviously had an impact on earnings which are set to miss the target by 9 per cent or a massive Rs 17,000 crore.

No end of trouble

The secular trend in the railways’ earnings is so disappointing that none expects the national carrier’s performance to improve in the coming financial year (2017-18). Hence the operating ratio for the year has been set at 94.6 per cent, virtually the same as that in the current year.

The second reason why the transition is ill-timed is because lately the railways have witnessed a string of accidents. To set things right, what is needed is focused handling enabled by both financial resources and management attention. The predominant cause of these appears to be derailment, which points to aging railway tracks giving up because they have not been replaced on time. The last time an arrear in track renewal built up, the government of the day sought to set it right by creating a Special Railways Safety Fund (SRSF). Consequently in 2001 the so called first SRSF was created and allocated Rs 17,000 crore. This was made up of Rs 12,000 crore from the central government and Rs 5,000 crore from the railways themselves by levying a safety surcharge.

Taking note of the need for renewal and safety, the government has announced in the Budget the creating of a Rs 1 lakh crore Rashtriya Rail Sanraksha Kosh or SRSF2 which will be spent over five years. The figure is impressive but under current conditions is likely to remain only on paper. This is because the government or the general exchequer is to provide only a bit of “seed capital” and the railways will have to arrange the “balance resources from their own revenues and other sources.” But where will the railways’ own resources come from when the operating ratio is so high and, according to the railways own expectations, likely to remain so? Borrowing will bring in some resources but at a high cost. Servicing such borrowing will eat into resources available for investment further.

One way out will be to levy a safety surcharge but that is another name for raising passenger fares. The scope for raising either passenger fares or freight rates is severely limited by the stagnation in traffic (number of passengers actually went down over a period and freight tonnage now seems to be similarly headed). What this has done is made infructuous one reform that has long been sought: setting up an independent authority to fix fares and freights so that these do not fall prey to populism or bad economics.

One, the railways are in extremely poor financial health. The operating ratio (gross operating expenses to gross earnings) is expected to touch a low of 94.9 per cent in the current financial year. Even if this revised estimate figure holds, which it may not, it means that virtually all that the railways earn is gobbled up by meeting its running expenses, thus leaving precious little for investment from its own resources. Expenses have shot up because of the government’s decision to implement the Seventh Pay Commission’s recommendations during the current financial year.

While a pay commission is set up around once in a decade and thus contributes to only a periodic spurt in expenses (after that there is a plateauing out at a higher level), earnings should follow a steady upward trajectory. It is here that the situation is most disturbing. For the first time in its history, the railways are set to end the year (2016-17) with freight loadings not just missing the target set for the year but actually going down to 1,093 million tonnes form the 1,101 million tonnes achieved in the previous year (2015-16). This has obviously had an impact on earnings which are set to miss the target by 9 per cent or a massive Rs 17,000 crore.

No end of trouble

The secular trend in the railways’ earnings is so disappointing that none expects the national carrier’s performance to improve in the coming financial year (2017-18). Hence the operating ratio for the year has been set at 94.6 per cent, virtually the same as that in the current year.

The second reason why the transition is ill-timed is because lately the railways have witnessed a string of accidents. To set things right, what is needed is focused handling enabled by both financial resources and management attention. The predominant cause of these appears to be derailment, which points to aging railway tracks giving up because they have not been replaced on time. The last time an arrear in track renewal built up, the government of the day sought to set it right by creating a Special Railways Safety Fund (SRSF). Consequently in 2001 the so called first SRSF was created and allocated Rs 17,000 crore. This was made up of Rs 12,000 crore from the central government and Rs 5,000 crore from the railways themselves by levying a safety surcharge.

Taking note of the need for renewal and safety, the government has announced in the Budget the creating of a Rs 1 lakh crore Rashtriya Rail Sanraksha Kosh or SRSF2 which will be spent over five years. The figure is impressive but under current conditions is likely to remain only on paper. This is because the government or the general exchequer is to provide only a bit of “seed capital” and the railways will have to arrange the “balance resources from their own revenues and other sources.” But where will the railways’ own resources come from when the operating ratio is so high and, according to the railways own expectations, likely to remain so? Borrowing will bring in some resources but at a high cost. Servicing such borrowing will eat into resources available for investment further.

One way out will be to levy a safety surcharge but that is another name for raising passenger fares. The scope for raising either passenger fares or freight rates is severely limited by the stagnation in traffic (number of passengers actually went down over a period and freight tonnage now seems to be similarly headed). What this has done is made infructuous one reform that has long been sought: setting up an independent authority to fix fares and freights so that these do not fall prey to populism or bad economics.