Three men from that group dropped out prematurely, while the rest — Adi Hakim, Jal Bapasola and Rustom Bhumgara — returned to India in 1928. The journey inspired two similar, more ambitious attempts. Framroze Davar, a sports journalist, pedalled alone to Austria in 1924, where he met and journeyed with cyclist Gustav Sztavjanik for seven years, adding South America to the list of continents covered. A third group — Keki Kharas, Rustom Ghandhi and Rutton Shroff — that travelled between 1933 and 1942 furthered the itinerary to include Australia.

The endurance cycling bug bit Indians at the turn of the century, likely after learning of European and American expeditions. A cycling culture took hold particularly among Bombay’s Parsis and Calcutta’s bhadralok, who were influenced by British ways and were wealthy enough to import bicycles like the Royal Benson or the Enfield. It remained in vogue until the 1940s, at least, when cars made an entry.

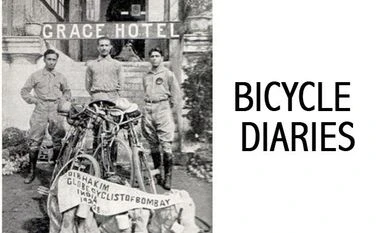

Keki Kharas, Rustom Ghandhi and Rutton Shroff in New York

Babani, also a serious cyclist, became curious about these Parsi rovers in 2017 when an injury forced him to rest and he began studying the history of the sport in India. It took him more than a year to establish contact with families of the cyclists and source around 30 rare photographs, which were exhibited last November in Goa, where Babani now lives. He is working on a book too. His collection of pictures, which has since grown to 60, will be displayed in Mumbai at a show titled “Our Saddles, Our Butts, Their World”.

Framroze Davar and Gustav Sztavjanik in Peru

Apart from being fascinating examples of endurance athletics, the episodes led to important documentation. Once in Europe, the cyclists sourced cameras and took pictures. “They saw a Europe ravaged by war. I don’t think any other Indians roamed the streets of the continent between the First and Second World Wars,” says Babani. The first group’s writings were published as a book, With Cyclists around the World. In his diaries, Davar, who travelled to the Sahara Desert and Amazon rainforest, wrote in anthropological fashion about the tribals he stayed with.

There are accounts also of how they tackled sandstorms, blizzards and the many toll collectors, and how they learnt to keep to the railway tracks to avoid getting lost in the desert. In places like Afghanistan, people still viewed bicycles as a novelty. The tour of China, hit by bad roads and political turmoil, slowed the first group by five months. Mistaken for spies, they were even imprisoned at times — the first group in Genoa, Italy, and the last in Iran.

The bicyclers, trained either as Boy Scouts or in the Bombay Weightlifting Club, appear in many of the photographs in athletic khaki outfits. Starting out with sums of Rs 1,000-2,000 each, they came up with inventive ways to raise more funds — doing odd jobs, selling souvenir cards and performing daredevil stunts like pulling a car with one’s teeth. Everywhere they went, the cyclists were invited to give lectures about their experiences and feted with money and medals.

Davar after crossing the Sahara desert

Some Indian newspapers excitedly reported their deeds. It provided opportunities for endorsement too. Dunlop Rubber, in a vintage print advertisement, included a signed letter wherein the first trio declared approval for the firm’s tyres. On reaching Bombay, the second duo, “Scouter Davar” and the Austrian Sztavjanik, projected pictures of the people and places they visited and exhibited curios they had collected.

The paramount object of these cyclists had been to show that in the realm of sports, they were equal to their Western brothers. “They talked about being the real sons of ‘Mother India’, and wanted to show how great India is,” observes Babani. “A national fervour was very much there. Not the kind of nationalism that is being touted today but a more serious nationalism because India was still part of the British empire.”

Following those early adventures, several of them took up jobs and started families. Notably, Bhumgara, a Leftist, plunged himself into the freedom movement and was jailed in Yerawada, Maharashtra. Davar is known to have practised cycling later in life, even when he lost his vision. Thereafter, says Babani, they remained largely “unsung”, unlike Sztavjanik whose compatriots built busts and started cycle tours in his name. The resurgence of enthusiasm for cycling in India, he hopes, will spur interest in recognising them as pioneers.

‘Our Saddles, Our Butts, Their World’ will show at the Piramal Gallery, NCPA, from May 10 to 14

)