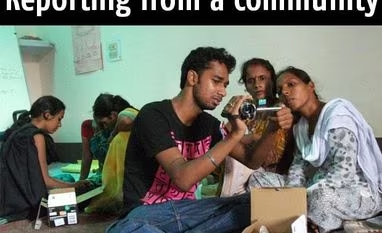

In a world where “citizen journalism” has come to refer to the often biased, undisciplined and sometimes “accidental” videos shot by common people, VV has created a scalable media platform in which each published video fits into the overall editorial plan. A total of 249 correspondents across 192 districts have been carefully selected by Mayberry and fellow founder of VV, Stalin K. They undergo a week of residential training, annual follow-ups and continuous mentorship to enable them to identify issues worth telling the world about. They’re paid between Rs 700 and Rs 7,000 depending on the complexity, length and impact of the video. With increased smartphone and internet penetration, this year VV is trying out an online training module that could enable them to train about 300 new correspondents in 2018. “Our key programme is India Unheard, through which community correspondents from each state in India report on issues ranging from corruption to local culture, which enables a global web audience to learn about issues of human rights and poverty directly from those who live it,” says Mayberry, estimating they receive about three million views a month.

What sets apart VV’s reports is that they encourage viewers to directly call the officials mentioned in them and exhort them to take action, or share them on social media. To incentivise the barefoot journalist to produce more impactful stories, VV pays more for videos that generate a response from the audience. So far, 1,318 of their 6,954 stories have convinced viewers to make those calls, and generate positive outcomes. VV has received several awards, including the NYU Stern Business Plan Competition, Manthan Award and the Knight News Challenge.

Presently, VV has an annual budget of Rs 30 million and spends about Rs 60,000 annually to support a single correspondent. They function on grants from agencies such as the Azim Premji Foundation. Additionally, they also have tieups with media houses, including NDTV, The Wire and CNN-IBN. On the anvil are plans to take this hyper-local news farther afield, so that viewers far away in New Delhi or even New York can become involved in the process of social change.

However, to link reportage directly with community-powered action can, sometimes, be disheartening. On September 27, 2017, Santoshi Kumari, an 11-year-old Dalit girl from a village in Jharkhand, reportedly died of starvation. A month earlier, a VV correspondent had shot a video on the issue of how many people in that very village didn’t have usable ration cards, but it fell on deaf ears. If someone in authority had taken notice of it, perhaps the girl may not have died… Mayberry and her band of committed barefoot journos have kept going on, convinced that, somehow, they’re on the right track. “I believe that VV’s community correspondents are a part of the greater movement towards transparency,” she says. “They tell their own stories, their own truths — and are, consequently, able to transform their own communities...”

To learn more or contribute, visit www.videovolunteers.org or follow them on Twitter and Facebook

Next, a unique night walk is enabling people to experience Delhi through the eyes of the homeless

)