The art of unification

The popular nationalistic upsurge led to Abanindranath Tagore rejecting his training in Western art practice in search for one that was more indigenous

)

premium

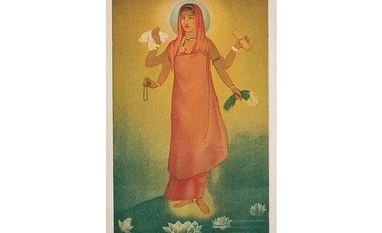

Abanindranath Tagore’s Bharat Mata, an iconocisation of India as motherland, became a unifying image for freedom fighters of the time

Did art play a role in the making of India’s republic? Its independence? It might surprise readers to note just how significant art was to prove in both cases, even though those contributions now remain neglected by an ill-informed society.

One of the critical elements in the struggle for freedom was forging a national identity in a country riven by language, consisting of over 500 princely states and Crown-administered provinces. From reformists and philosophers to writers, poets and politicians, they struggled to find a common, unifying cause in a country that was culturally knit together without the perspective of a unified whole. It was into this chasm that the self-taught artist Raja Ravi Varma stepped in to give India an iconography for its gods, goddesses, historical heroes and mythological heroines, leading to the creation of a pan-national image to which anyone could lay claim. This effort would have been in vain, however, were it not for a colour printing press he acquired, soon churning out these images to sell in bazaars and around temples. The prints became a rage, and the Himachali, the Maharashtrian and the Bengali were quick to take them home as icons for both their puja rooms and their living rooms.

The popular nationalistic upsurge led to Abanindranath Tagore rejecting his training in Western art practice in search for one that was more indigenous, thereby laying the roots of what came to be known as the Bengal “School”. His subjects came from India’s cultural moorings, but most importantly, his painting of Bharat Mata — an iconocisation of the country as motherland — became a unifying image for the freedom fighters of the time. The demand for freedom went beyond provincialities to embrace all of India.

One of the critical elements in the struggle for freedom was forging a national identity in a country riven by language, consisting of over 500 princely states and Crown-administered provinces. From reformists and philosophers to writers, poets and politicians, they struggled to find a common, unifying cause in a country that was culturally knit together without the perspective of a unified whole. It was into this chasm that the self-taught artist Raja Ravi Varma stepped in to give India an iconography for its gods, goddesses, historical heroes and mythological heroines, leading to the creation of a pan-national image to which anyone could lay claim. This effort would have been in vain, however, were it not for a colour printing press he acquired, soon churning out these images to sell in bazaars and around temples. The prints became a rage, and the Himachali, the Maharashtrian and the Bengali were quick to take them home as icons for both their puja rooms and their living rooms.

The popular nationalistic upsurge led to Abanindranath Tagore rejecting his training in Western art practice in search for one that was more indigenous, thereby laying the roots of what came to be known as the Bengal “School”. His subjects came from India’s cultural moorings, but most importantly, his painting of Bharat Mata — an iconocisation of the country as motherland — became a unifying image for the freedom fighters of the time. The demand for freedom went beyond provincialities to embrace all of India.

Abanindranath Tagore’s Bharat Mata, an iconocisation of India as motherland, became a unifying image for freedom fighters of the time