The everyman performer

The authors take us through some engaging anecdotes from Kumar's personal life

)

premium

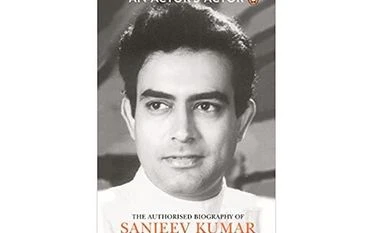

Book Cover (An actor’s actor – The authorized biography of Sanjeev Kumar)

5 min read Last Updated : Feb 04 2022 | 12:10 AM IST

An actor’s actor – The authorized biography of Sanjeev Kumar

Author: Hanif Zaveri and Sumant Batra

Publisher: Penguin Ebury Press

Pages: 216

Price: Rs 599

You never noticed him. That was the brilliance of Harihar Jethalal Jariwala a.k.a Sanjeev Kumar. He was Aarti Devi’s estranged husband in Gulzar’s Aandhi (1975) or Dr Amarnath who discovers his old flame’s daughter in a brothel in Mausam (1975) or the mentally ill Vijay in Chander Vohra’s Khilona (1970). These are just three of about 170 films that Kumar did. In every one of them he did not act — he performed. It was not his walk, his talk or a stylish mannerism that earned him his stardom: It was simply his performance. That is why he’s acknowledged as one of the finest actors in Indian cinema. He died of heart trouble at 47, much before he had exhausted his range and versatility. That is why An Actor’s Actor, Kumar’s authorised biography by film writer Hanif Zaveri and lawyer Sumant Batra, is a big draw for me.

It begins with the story of his parents’ marriage (his mum Shantaben was Jethalal’s third wife), their financial troubles and the death of Kumar’s dad when he was just 11 years old. He was moved from an English medium school to a Gujarati one. The family of five lived in one room, and money was short. It was the lack of space at home that forced him to stay back at school to do his homework in a room that his teacher C H Intwala offered. He taught maths, science and dramatics. Kumar and Intwala discovered that they shared a mutual interest in theatre and dramatics. In plays written and performed by the students Hari (Kumar) became an enthusiastic participant. Shantaben was appalled to hear of his interest in acting. She confronted Intwala and accused him of ruining Hari’s prospects. In the fifties, medicine, engineering or the Indian Administrative Service were the only professions to which to aspire.

Intwala heard her out. He then pointed out that Hari was a good student, he attended school regularly and was on the right path for success. But he was also a wonderful actor. Being his dramatics teacher, Intwala was just encouraging it. Eventually, Shantaben did give in to Hari’s strong desire to be engaged with the arts. It was her jewellery that provided him the money to join P D Shenoy’s acting classes at Filmalaya. His journey from there to Gujarati theatre, then Indian People’s Theatre Association (IPTA), his struggle to get accepted into Hindi cinema and the many misses he had before his first successes, Sanghursh (1968) and Anokhi Raat (1969), are interesting to read about.

His non-starriness in a profession where looks mattered and his love of the kurta-pyjama meant directors rejected him all through the fifties and well into the mid-sixties. But it was exactly this attitude that allowed him to take on and shine in roles like Trishul (1978), Mausam or Koshish (1972). He did not have an image or a style. He was whichever character you wanted him to be. For someone who never lived to see old age, Kumar played the part of an old man frequently. Among his first stage plays was Damru where he played a 60-year old. He was 19 then.

The authors take us through some engaging anecdotes from Kumar’s personal life. His relationships with actor Nutan and later with Hema Malini and why those came to naught, his close friendship with Shatrughan Sinha who has written the foreword to this book and his complete lack of inhibitions about his body. One of the most popular Kumar numbers, Thande Thande Paani Mein from Pati, Patni aur Woh (1978), has a potbellied Kumar frolicking in the bathroom with his on-screen son.

What the book misses is a feel for Kumar’s craft. There is almost nothing about how he thought of acting, his view on the roles he played or on cinema. This is the biggest issue with this well-intentioned and diligently put together book. It is a good chronicle of Kumar’s life which focuses, somewhat excessively, on his family history. But it is painfully devoid of any insight into why the book is being written — his films. You could argue that Kumar died in 1985, more than 35 years before this book. Without him and many of the filmmakers he worked with, the writers might have had trouble with the research. Maybe.

The other issue is some sweeping statements that jar. For instance, while talking about the rejection he faced in his initial years, the writers say, “It was an industry steeped in nepotism and he was a rank outsider with no money to spare for even a new set of clothes.” But in the fifties everyone was a first-generation actor — Dilip Kumar, Dev Anand, Ashok Kumar, Nargis or Vyjanthimala Bali. Except for Prithviraj Kapoor’s and possibly Shobhana Samarth’s there was no film family. Now that there are third generation actors in Indian cinema you could say that there are cases of an actor’s child getting easier access.

However, like me, you could choose to ignore these. Just read the book to get as much information as possible on a man who brought us so much joy through his work.

Topics : BOOK REVIEW Literature