The emperor who could not be

Interest in Dara Shikoh reflects current trend to differentiate hardline Islam from tolerant Islam

)

premium

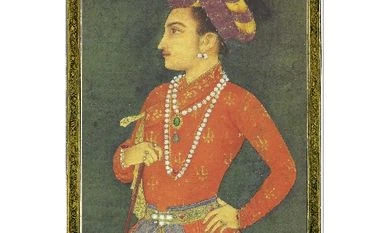

A portrait of Dara Shikoh believed to have been painted by Murar in 1631; a map depicting the wars of succession between Shah Jahan’s sons that led to Aurangzeb’s victory

In February this year, a road in Lutyens Delhi shed its 19th century colonial persona to go back about three centuries to its Mughal past. Dalhousie Road, just a couple of kilometres from Raisina Hill, was renamed Dara Shikoh Road, after Mughal Emperor Shah Jahan’s eldest son. It would seem like poetic justice, considering another road named after his brother, Aurangzeb, was renamed APJ Abdul Kalam Road in 2015. “Justice”, as a Twitter user pointed out, would have been more direct had Aurangzeb Road been renamed after his elder brother.

The sibling rivalry between the two Mughal princes is both legendary and mythic. Legendary because many scholars and historians believe that had Dara Shikoh ascended to the throne as his father intended, India’s history would have been shaped very differently. And, mythic because the almost simplistic manner in which Aurangzeb is seen as a villain and Dara Shikoh as the victim of his own yielding nature has moulded historical narratives and common perception. But this simplistic dichotomy has only propelled more interest in the figure of Dara Shikoh, especially among historians, students and cultural organisations. Last month, the Indian Council for Cultural Relations (ICCR) held a symposium dedicated to Dara Shikoh, his Sufi legacy, and the eternal question of “what if”.

“India would have had a constitutional monarchy had Dara Shikoh become emperor,” says Lokesh Chandra, president of ICCR, with an air of certainty. “He was a strong believer in the peaceful co-existence of various cultures. Had he not lost the Battle of Samugarh (1658), the Mughal kingdom and India would have had a more tolerant Islam.” This, he says, would have eventually not been attractive to the British empire, because Queen Victoria would not have wanted a colony that equalled her in stature and would, in turn, not be subservient to the crown.

The sibling rivalry between the two Mughal princes is both legendary and mythic. Legendary because many scholars and historians believe that had Dara Shikoh ascended to the throne as his father intended, India’s history would have been shaped very differently. And, mythic because the almost simplistic manner in which Aurangzeb is seen as a villain and Dara Shikoh as the victim of his own yielding nature has moulded historical narratives and common perception. But this simplistic dichotomy has only propelled more interest in the figure of Dara Shikoh, especially among historians, students and cultural organisations. Last month, the Indian Council for Cultural Relations (ICCR) held a symposium dedicated to Dara Shikoh, his Sufi legacy, and the eternal question of “what if”.

“India would have had a constitutional monarchy had Dara Shikoh become emperor,” says Lokesh Chandra, president of ICCR, with an air of certainty. “He was a strong believer in the peaceful co-existence of various cultures. Had he not lost the Battle of Samugarh (1658), the Mughal kingdom and India would have had a more tolerant Islam.” This, he says, would have eventually not been attractive to the British empire, because Queen Victoria would not have wanted a colony that equalled her in stature and would, in turn, not be subservient to the crown.

Shah Jahan with his ‘favourite’ son, Dara Shikoh, in this painting taken from a leaf of an album made for Shah Jahan in 1620