Delhi's Greater Kailash constituency highlights complexity of urban governance

India's extremes of diversity and exclusion work together to make urban governance far more complex than it need be

)

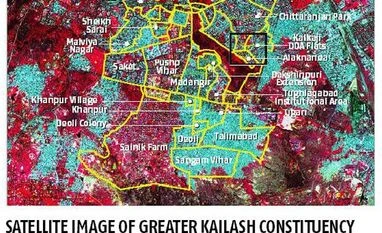

Greater Kailash (GK) was originally a plotted development by DLF through, what would now be called, PPP mode. This land was given by the government to the private sector operator, whereas the bulk of the urban planning and plotted development was done by DLF, under norms and parameters specified by the government. The plots were then sold and infrastructure upkeep was with the government. Greater Kailash (GK) was initially planned as an extension to the earlier ‘brand’ of Kailash Colony. The neighbourhood soon achieved a brand of its own and surrounding areas also wanted to hitch a ride on this brand-wagon. Soon, we had GK 1, GK2, GK3, GK4, GK Enclave 1, GK Enclave 2, GK Extension and other variants of the original brand around the area. The legislative constituency is now called Greater Kailash constituency and also contains other neighbourhoods like Sainik Farms, Chittaranjan Park, Alakananda DDA apartments, etc.

Greater Kailash is undoubtedly among the more affluent parts of urban India but the constituency also contains Sangam Vihar and the Talimabad slums, which are among the lowest income areas of Delhi. Alakananda is a complex of flats originally built by the Delhi Development Authority under its Self Financing Scheme for the middle class. Right next door would be Kalkaji, the bulk of which is resettled immigrants from West Pakistan. CR Park, residents comprising migrants from what was then labelled as East Pakistan. South-west of that is Sainik Farms where farmland was divided up into smaller residential areas without appropriate reasoning. The languages, culture of engagement, character, expectations and needs all differ widely within the area.

The area that falls under Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) Member of Parliament Meenakshi Lekhi’s constituency is represented by AAP MLA Saurabh Bharadwaj. Its four wards are represented by councillors from both Congress and the BJP. Across India, multiple tiers, multiple parties, and staggered elections, frequently throw up such diverse political power centres and coordination becomes problematic. Especially so as elected representatives willing to work with others are often accused of selling out within their own parties.

The government servants that serve or oversee this area follow a soul-less standardised process, blind to the variations in economy, society or demography within the area. Some involved in law and order report to the central government, some such as the public works department report to the city government, and yet others such as garbage collection are overseen by the municipal corporation. Within each of these, the officer in charge is overloaded and under-resourced. More, she follows a highly structured mandate, with no flexibilities or power. In other words, the only thing the functionary can do is follow the process.

The intervention of the local politician —‘local elder’ — strongman nexus helps the government functionary incorporate the specific needs of specific communities. This intervention is not only via a side payment and could include threats or quid pro quos. The illegality and immorality of this politician-strongman-local elder nexus helps substitute for an organisational design failure. In other words, because governance structures are straightjacketed, whereas the requirement is one of flexibility, the local politician/strongman uses extra-legal and informal pressure tactics to help meet the immediate needs of diverse communities in his area. Of course, he also extracts his monetary or non-monetary premiums in the process. The latter enables him to sustain his work. In yet other words, immorality is inherent in local political processes because government processes are not flexible enough.

Also Read

Of all of this cultural and economic diversity, what is perhaps most important is the coexistence of massive slum and affluent areas. Within affluent areas as well, household help, occupants of illegal shacks, construction workers and various service providers live next door to the highly affluent. In low income areas as well, affluent shop and small business owners, local leaders, etc, have incomes at par with those of the affluent. This is a generic phenomenon in India and has some significant economic advantages. Proximity of low income to the affluent enables generation of various income earning options for the poor. Proximity also eases access of the poor to good infrastructure. Cross-subsidisation of water, gas and electric services becomes easier. More, proximity enables lower retail costs – and therefore a large proportion of day-to-day retail and service purchases of affluent and middle class households are sourced from nearby low income neighbourhoods.

The planned and typically affluent areas also have an illegal space rental system, meant for the poor to carry out their occupations. Maids and vendors pay to walk across certain short cuts, street vendors, paanwalas, cycle mechanics, presswalas, sabziwalas, plumbers and electricians all pay for their patch. Of course, the poor are harassed and are made to pay but they add these costs to their affluent and middle class clients. While we can decry the immorality of all this, and we should, atleast the poor get some avenues for both living and livelihood.

There is a lot that needs to be corrected, and the flavour of correction will be different in every area. Therefore, the decentralised approach is the only one that can work. One way of decentralising is to strengthen the ability of community driven organisations such as Resident Welfare Associations (RWAs) and Market Associations (MAs). This also entails making local governance more answerable to such community-rooted entities – a directly elected mayor who directly oversees the municipal commissioner and all of local government is one obvious solution. This will automatically reduce the power of the standardised, one-size-fits-all process that has failed India.

More From This Section

Don't miss the most important news and views of the day. Get them on our Telegram channel

First Published: Oct 16 2016 | 11:59 PM IST