PNB scam: Why do we not talk about the whopping bank loan defaults?

It's high time CFOs pull their socks and perform fearlessly

)

premium

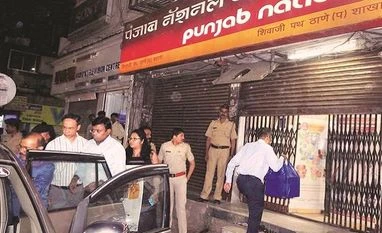

The fraud at Punjab National Bank (PNB) has aroused a lot of indignation and angst. The amount in question is Rs 130 billion, a measly sum compared to banks’ non-performing assets (NPAs) of Rs 8.5 trillion. Of the NPAs, the top 12 stressed assets account for Rs 2.5 trillion while 488 defaulting companies make up the rest.

Then, why are these loan-defaulting companies’ promoters not being called fraudsters? In our eyes, these are shown simply as loan defaults or NPAs. In the PNB case, everyone—from the government to the Reserve Bank of India (RBI) to the PNB management—is indulging in the blame game and the company’s management is denying any wrongdoing.

As it has been in the past, this time too, the employees will be made the scapegoat while the promoters escape. Considering the slowness of the legal system, it would be a surprise if they are punished.

Why do public sector banks (PSBs) have most of the bad loans? Does the government not intervene in their functioning? Why are proper processes not followed before loans are sanctioned? Why is the liquidation value of these assets very low compared to net asset values? Why do bank managements ignore the red flag raised by statutory auditors and the rating agencies? Questions are many but no concrete answers are available.

Typically, a bank goes through several audits such as statutory audit, internal audit, concurrent audit, Reserve Bank audit, stock audit, and so on. Why can’t auditors spot lapses? It is surprising that despite half-a-dozen auditors and surveillance agencies and the IT system, fraudulent activities continue for years on end.

Why do our chief financial officers (CFOs) not act in the way their job demands? A few instances bring shame to the profession. It’s high time CFOs pulled up their socks and performed fearlessly. Their performance in a financial control mechanism should be such that while the management sweats, the organisation runs seamlessly.

Then, why are these loan-defaulting companies’ promoters not being called fraudsters? In our eyes, these are shown simply as loan defaults or NPAs. In the PNB case, everyone—from the government to the Reserve Bank of India (RBI) to the PNB management—is indulging in the blame game and the company’s management is denying any wrongdoing.

As it has been in the past, this time too, the employees will be made the scapegoat while the promoters escape. Considering the slowness of the legal system, it would be a surprise if they are punished.

Why do public sector banks (PSBs) have most of the bad loans? Does the government not intervene in their functioning? Why are proper processes not followed before loans are sanctioned? Why is the liquidation value of these assets very low compared to net asset values? Why do bank managements ignore the red flag raised by statutory auditors and the rating agencies? Questions are many but no concrete answers are available.

Typically, a bank goes through several audits such as statutory audit, internal audit, concurrent audit, Reserve Bank audit, stock audit, and so on. Why can’t auditors spot lapses? It is surprising that despite half-a-dozen auditors and surveillance agencies and the IT system, fraudulent activities continue for years on end.

Why do our chief financial officers (CFOs) not act in the way their job demands? A few instances bring shame to the profession. It’s high time CFOs pulled up their socks and performed fearlessly. Their performance in a financial control mechanism should be such that while the management sweats, the organisation runs seamlessly.

Disclaimer: These are personal views of the writer. They do not necessarily reflect the opinion of www.business-standard.com or the Business Standard newspaper