Public debt in India - II

The security level analysis shows that the large contribution of nominal returns poses a potential risk for unstable debt-GDP dynamics in India

)

premium

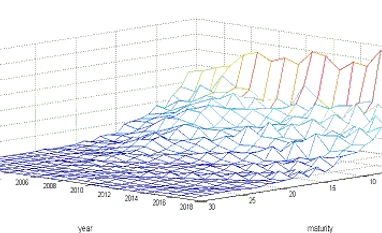

Figure: Nominal payouts as a share of GDP by year and maturity of debt for Centre

Public debt sustainability is the ability of a government to maintain credible public finances that are serviceable and can support robust economic growth in the long run. In part one of this two-part series, we had emphasised that the large contribution of nominal interests pose a challenge to debt management in India. One problem with using aggregate data on public debt means that we can’t exploit the maturity structure of debt and its impact on the interest rate component. It should be pointed out however that any debt-decomposition analysis using aggregate debt has an important drawback: It leaves residuals unaccounted for. Measurement errors in GDP as well as the deficit numbers contribute to the residual component, and this leads to a less accurate portrait of the drivers of public debt.

In our recent research, we therefore extend the aggregate debt analysis by undertaking a Hall-Sargent debt decomposition using a novel granular Centre-State security level dataset for India that we have assembled from 2000-2018. The Figure below shows the nominal payouts as a share of GDP by year and maturity just for Centre securities from 2000-2018. Our analysis show that since 2010, there has been a gradual decline in the maturity of the debt raised by the Centre. In 2018, the highest maturity for payouts as a share of GDP is 15 years so that most of the debt that is due is below 15 years.

In our recent research, we therefore extend the aggregate debt analysis by undertaking a Hall-Sargent debt decomposition using a novel granular Centre-State security level dataset for India that we have assembled from 2000-2018. The Figure below shows the nominal payouts as a share of GDP by year and maturity just for Centre securities from 2000-2018. Our analysis show that since 2010, there has been a gradual decline in the maturity of the debt raised by the Centre. In 2018, the highest maturity for payouts as a share of GDP is 15 years so that most of the debt that is due is below 15 years.

Figure: Nominal payouts as a share of GDP by year and maturity of debt for Centre

Disclaimer: These are personal views of the writer. They do not necessarily reflect the opinion of www.business-standard.com or the Business Standard newspaper

Topics : Public debt India GDP growth Finance Ministry