Coal shortages are back: Low productivity of CIL haunts sector

Even as the government gets ready for commercial auction of mines, the low productivity of Coal India haunts the sector

)

premium

Last Updated : Oct 03 2017 | 10:52 PM IST

Last month, ten companies that transport sand to and coal from Western Coalfields, a subsidiary of Coal India Limited (CIL), were fined Rs 11.8 crore for rigging bids to win the contracts. The Competition Commission of India order, on a complaint by the Mini Ratna company, also imposed fines on eight officials of these operators. These companies are among hundreds that dot Nagpur and nearby towns, running on low-technology operations that earn high returns by exploiting shortages.

The irony of this scandal is that it reflects the persistent shortfall in coal supply even after the Supreme Court’s landmark verdict three years ago, designed to prevent suppliers from gaming shortages. That verdict cancelled all coal mine allotments made since 1993, the year the central government began handing them out after amending the Coal Mines (Nationalisation) Act. The court held that no consistent rules were laid down to decide the allotments. Thus, maverick operators got mines free but sat on them to leverage supply shortages.

Since the verdict, there have been huge changes in the coal sector. Of the 204 coal block allocations that the Supreme Court cancelled in September 2014, the Centre auctioned 31 of them for captive use. In March this year, the coal ministry sought public reaction to a plan to auction blocks for commercial mining. Reports say 10 coal blocks in four states will go under the hammer in the first phase, though no dates have been set.

All this has certainly improved perceptions about coal policies. The government has been able to demonstrate the existence of a transparent set of rules for the sector. Over the lifetime of the mines, states where the coal mines are located will earn Rs 1,96,698 crore, says a ministry note.

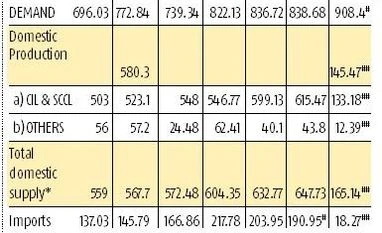

Yet coal shortages have returned to haunt the economy. CIL data shows consumers bought 7.2 per cent more coal in August 2017, year-on-year. But the compound growth rate of annual production, even assuming CIL meets its target of 600 million tonnes by March 2018, will be only 6.73 per cent.

In March this year, the competition regulator fined Coal India Rs 591.01 crore for exploiting the shortages by unilaterally imposing stiff fuel supply agreement terms on power producers, rather than through bilateral discussion. To its credit, the ministry under Piyush Goyal, has since drawn up a revised coal allocation policy, termed Shakti — Scheme for Harnessing and Allocating Koyala Transparently in India (sic).

Although Shakti created an eco-system to harness coal fairly, the ministry has not moved to improve the endemic inefficiencies in coal mining. As former coal secretary P C Parakh pointed out, CIL is not an efficient coal miner. Output per man shift at 5.62 tonnes in 2014-15 is an eighth of Peabody, one of its international rivals. The slack in production by CIL (see table) cannot be filled by private sector competitors who have won at the auctions. Only ten of those blocks have resumed operations.

Meanwhile, hardening international prices have crimped the options for bridging shortages through higher imports. By late 2015, growing global distaste for coal-fired electricity saw coal price per tonne dip below $25. Since then, Reuters noted, “Australian coal cargo prices for export from its Newcastle terminal hit a 2017 high of $103.5 per tonne at their last close, driven by strong Asian demand” (the Newcastle contract is the benchmark for Asian thermal coal prices).

So, this September, just as it was doing four years ago, the ministry finds itself monitoring coal supply from CIL for thermal power plants on a daily basis. On September 17, it issued a press note to acknowledge that 17 power plants (out of 184) had seen coal stocks dip perilously low, nine of them had just three days’ supply. The monsoon is always a bad time because the open cast mines, which account for more than 75 per cent of CIL’s production, become massive slush pools.

Last year, stocks with CIL were enough to keep the power plants running comfortably. The ministry had noted: “As on 31st March, 2016, the coal stock was 38.87 MT which is the highest in last four years”. Stocks available with power utilities in July were sufficient to operate the plants for 23 days.

That created a false sense of safety and possibly delayed further reforms.

This year, the acting CMD of CIL, Gopal Singh, says the 17 per cent rise in thermal power generation in August year-on-year is making up for a 12 per cent reduction in hydro-power generation and a 36 per cent cutback in nuclear power. This shortage has been compounded by another scarcity — railway wagons to transport coal from the mines to the plants.

The Railways, perennially short of funds, could not lay the lines needed to bring railheads closer to more mines or buy wagons to transport adequate amounts of coal on time to power, cement or steel plants. It began to make amends from 2014, constructing two dedicated lines in Jharkhand and Odisha — the 53.5 km Jharsuguda-Barapali rail link and the 9.5 km Tori-Shibpur line near Hazaribagh. But now coal minister Goyal is in “fire fighting” mode, pushing his other charge, the railways, to make available wagons on priority.

The brief sense of safety in supply also made the power companies adventurous. Coal stocks take up space and block capital. By gambling on storing less coal, the world’s largest power supply company, NTPC managed to cut its electricity production cost to Rs 1.94 in 2016-17 from an average of Rs 2.01 per unit in 2014-15.

NTPC is unlikely to match that number this financial year. The coal ministry had promised that dip in electricity prices would translate into a benefit of Rs 69,310.97 crore for consumers over the next few years. Rising coal prices could nullify some of that benefit — far more, in fact, than the gains extracted by the puny coal and sand mafia transporters.