When the Finance Bill goes beyond Budget making

The amendment of around 40 central statutes makes the Finance Bill, 2017 unique

)

premium

The passage of the Finance Bill, 2017, by the Lok Sabha on March 22 has rekindled the widespread debate over using a Money Bill to amend other pieces of legislation in the financial and general sphere. First introduced on February 1, the Bill has come under the scanner with critics voicing opinions on its all-pervasive nature and attempts by the BJP-led government to muscle changes into the legal framework without the nod of the upper house.

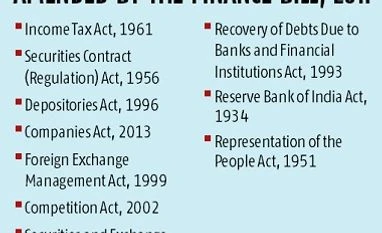

Finance Bills are annual features of Indian parliamentary democracy, used to adjust rates of taxation and bring changes in the fiscal structure. However, what makes the Finance Bill, 2017, unique is the sheer extent of the legislative changes proposed. The amendment of around 40 central statutes, many of which would have a tough time being classified as Money Bills if introduced separately, has taken this year’s exercise into highly uncharted territory.

Modifications making the Aadhaar mandatory for filing tax returns, capping cash transactions at Rs 2 lakh, the merger of several tribunals and increasing the authority of the central government in their governance, are examples of a few of these. The contentious issue of electoral bonds and relaxations of mandatory disclosures in line with political funding have also faced marked scepticism and scrutiny.

Last year the government had amended the Foreign Contribution (Regulation) Act, 2010, through the Finance Act, 2016, which drew the ire of civil society activists for having been passed through the money bill route.

Under the Constitution, a Money Bill is exempted from the usual rigours of a bicameral law-making process. As this exception renders the parliamentary functions of the Rajya Sabha to those of a concerned spectator, the law has been careful in defining what constitutes a Money Bill. Under Article 110 of the Constitution, a Bill can be classified as a Money Bill only if it (i) imposes, alters, abolishes or regulates any tax; (ii) regulates borrowing or alters the financial obligations of the government; and (iii) affects the custody of the Consolidated Fund of India or appropriates payments, withdrawals and expenditures from the fund and matters incidental to all these actions.

Article 110(3) further states that the decision of the Speaker of the lower house shall be final for all questions on whether a Bill is a Money Bill or not. This assertion in the Constitution has led to many, including Subhash Kashyap, constitutional expert and former secretary general of the Lok Sabha, to opine that the classification of a Money Bill falls outside the purview of judicial review. “The Speaker is to certify a Bill as a Money Bill. There is no appeal to this in a court or any other judicial forum,” says Kashyap.

Finance Bills are annual features of Indian parliamentary democracy, used to adjust rates of taxation and bring changes in the fiscal structure. However, what makes the Finance Bill, 2017, unique is the sheer extent of the legislative changes proposed. The amendment of around 40 central statutes, many of which would have a tough time being classified as Money Bills if introduced separately, has taken this year’s exercise into highly uncharted territory.

Modifications making the Aadhaar mandatory for filing tax returns, capping cash transactions at Rs 2 lakh, the merger of several tribunals and increasing the authority of the central government in their governance, are examples of a few of these. The contentious issue of electoral bonds and relaxations of mandatory disclosures in line with political funding have also faced marked scepticism and scrutiny.

Last year the government had amended the Foreign Contribution (Regulation) Act, 2010, through the Finance Act, 2016, which drew the ire of civil society activists for having been passed through the money bill route.

Under the Constitution, a Money Bill is exempted from the usual rigours of a bicameral law-making process. As this exception renders the parliamentary functions of the Rajya Sabha to those of a concerned spectator, the law has been careful in defining what constitutes a Money Bill. Under Article 110 of the Constitution, a Bill can be classified as a Money Bill only if it (i) imposes, alters, abolishes or regulates any tax; (ii) regulates borrowing or alters the financial obligations of the government; and (iii) affects the custody of the Consolidated Fund of India or appropriates payments, withdrawals and expenditures from the fund and matters incidental to all these actions.

Article 110(3) further states that the decision of the Speaker of the lower house shall be final for all questions on whether a Bill is a Money Bill or not. This assertion in the Constitution has led to many, including Subhash Kashyap, constitutional expert and former secretary general of the Lok Sabha, to opine that the classification of a Money Bill falls outside the purview of judicial review. “The Speaker is to certify a Bill as a Money Bill. There is no appeal to this in a court or any other judicial forum,” says Kashyap.