Sócrates, the chain-smoking football genius

The book captures the insouciance, glory and contradictions of former Brazilian captain's life

)

premium

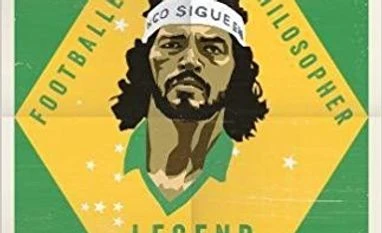

Doctor Sócrates, footballer, philosopher, legend; Author: Andrew Downie, Publisher: Simon & Schuster, Pages: 384, Price: £20

Scanning through Andrew Downie’s Doctor Sócrates: Footballer, Philosopher, Legend, you’re tempted to compare, for his affable smugness and towering persona, the former maverick Brazilian midfielder with another larger-than-life genius in Eric Cantona. In other parts, his incessant carousing and perilous womanising make you instantly think of George Best, who for all his paranormal talent, was always more interested in a sundowner or two than serious footballing matters.

On the pitch, however, Sócrates was both. He possessed the I-make-everyone-better virtuosity of Cantona and the defender-circling finesse and hubris of Best — a utopian world that joyously played out first on the sun-soaked streets of Ribeirão Preto in Sao Paulo, and then all across the world.

His personality was more complex. Football was just a hobby, celebrating goals — sometimes truly scintillating ones — wasn’t his thing, and friends would often be astounded at how quickly he could go from guffawing to discussing gravely serious matters, and then go back to making jokes again. And despite scoffing at all varieties of conformity, in the end, his own life turned out to be one despairing, drawn-out cliché.

On the pitch, however, Sócrates was both. He possessed the I-make-everyone-better virtuosity of Cantona and the defender-circling finesse and hubris of Best — a utopian world that joyously played out first on the sun-soaked streets of Ribeirão Preto in Sao Paulo, and then all across the world.

His personality was more complex. Football was just a hobby, celebrating goals — sometimes truly scintillating ones — wasn’t his thing, and friends would often be astounded at how quickly he could go from guffawing to discussing gravely serious matters, and then go back to making jokes again. And despite scoffing at all varieties of conformity, in the end, his own life turned out to be one despairing, drawn-out cliché.

Clockwise from top left: Junior, Sócrates, Cerezo, Zico, Edinho and Brazil manager Tele Santana