Shankar Acharya: A tiger cub in the neighbourhood?

A great deal needs to be done quickly & systematically if Myanmar is to realise its potential for agricultural growth

)

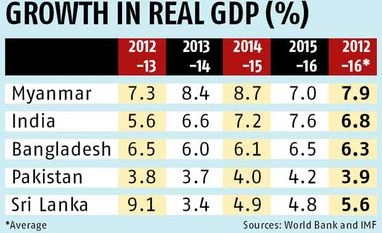

These days we are frequently told, usually by government ministers and spokes-persons, that India is the "fastest growing large economy in the world". Never mind that the debate on the new (since January 2015) national income data series, on which this claim is based, remains the subject of vigorous debate and scepticism. Many reputable, non-government analysts believe that "real" economic growth is probably one or two per cent points lower than the 7.5 per cent GDP growth indicated by the new series. Whatever the truth, we should perhaps be a little less self-focused and lift our attention to the new "tiger-cub-economy" in South Asia (taking a Curzonian view of that label), namely, Myanmar, with whom we share a 1,650-km land border and the Bay of Bengal and the Andaman Sea.

Political and economic reforms were launched in Myanmar in 2011, with the shift to a semi-civilian government (after 50 years of military rule) and a marked opening up to foreign trade and investment along with a loosening of the Western sanctions regime. In the four years since the financial year 2011-12, Myanmar's GDP growth has been significantly higher than India's and also much higher than that of Bangladesh, Pakistan and Sri Lanka. Clearly the star performer of South Asia. One has only to visit Yangon to get a flavour of the ongoing urban boom.

But therein lies the rub. Thus far the high growth seems largely confined to the urban-industrial-services complex, with little dynamism yet in Myanmar's rural countryside, where 70 per cent of the population live and where over two-thirds of the nation's labour force works primarily in agriculture.

According to the World Bank's most recent "Myanmar Economic Monitor" of October 2015, over half of real GDP growth in the years 2011-15 has come from the services sector, notably telecommunications (with SIM card costs falling precipitously from $250 to $1 in the two-and-a-half years from early 2013 to late 2015 and mobile penetration rates rising from less than 10 per cent in February 2014 to over 80 per cent at present), trade (external and domestic) and transport services. Industry has provided over a third of the total growth in this period, mainly attributable to gas development and construction activities, with light manufacturing making some headway in more recent years. Agriculture (including crops, livestock and fisheries), buffeted by variable weather and weighed down by massive legacy problems, has contributed barely 10 per cent of total economic growth in the four years up to 2014-15.

Myanmar's agriculture lags far behind its neighbours' in productivity (with income per agricultural worker about $200 compared to over $700 in Thailand and $500 in Bangladesh), distribution of tillage rights (all land is owned by government) is very unequal, 30-50 per cent of rural households are landless, 30 per cent of rural households live below a dollar-a-day per person poverty line, one-third of children under five are stunted and inadequate food availability afflicts nearly half of rural households a couple of months each year.1

It's a far cry from the 1950s when Burma (as Myanmar was then known) was a relatively prosperous agricultural economy and a world leader in rice exports. But the half century of poor policies and entropy in existing systems since 1962 has led to agricultural stagnation and a litany of woes which include: out-dated agronomic practices; low and inappropriate usage of fertilisers and pesticides; poor water control systems; high transportation costs; very weak rural credit systems; cumulatively low investment in agricultural research; bureaucratic and unresponsive extension services; unpredictable government policies and a long history of ethnic conflict in large areas of the country.

Yet, as reports like the MSU-MDRI study have pointed out, Myanmar's agricultural potential is enormous. Four major river systems run through the country (including the famous Ayeyarwady) and three of these originate within Myanmar, giving the country full control of water rights. These bountiful rivers supply 24,000 cubic metres per capita of renewable, fresh water per year, about 10 times the water levels available in China and India and double the water available in Bangladesh, Thailand and Vietnam. The country's strategic location between two water scarce giants, China and India, offers enormous long-term market potential for Myanmar. Furthermore, the diversity in topography and climate allows development of a wide range of crop and livestock products, while the long coastline and river systems hold great promise for fisheries.

To realise this tremendous potential, the MSU-MDRI study points to some "low-hanging fruit" such as increasing rice productivity through better cropping practices, improved seeds, greater water control, better use of fertilisers and pesticides and superior post-harvest milling, management and transportation/marketing; as well as diversification into high-value horticulture, poultry, fisheries and small livestock. All of these offer substantial income opportunities to small farmers and the landless, not just for large and medium farmers. In the longer-run, huge gains can be reaped through more agricultural research, revamped extension services, superior transport and communications, wider and deeper rural finance systems, much greater water control and irrigation, more secure and clearly defined tillage rights, much-improved data collection and dissemination systems, more and better access to education and health services and, of course, cessation of ethnic conflicts.

Some of these policy and institutional improvements have already begun. But a great deal more has to be done quickly and in a sustained and systematic fashion, if Myanmar is to realise her fortunate potential for rapid, broad-based agricultural development. The political mandate for such development was clearly rendered in the elections of last November. The challenge (a huge one) for the new government of the National League for Democracy, which assumed office last month, will be to master the wholly novel intricacies and pitfalls of governance, in a highly constrained constitutional and administrative framework, and translate the sweeping electoral mandate into well-functioning policies as soon as possible.

Only then will the tiger cub really roar.

1. See "A Strategic Agricultural Sector and Food Security Diagnostic for Myanmanr" by Michigan State University and Myanmar Development Resource Institute, July 2013 (MSU-MDRI Study)

The writer is honorary professor at ICRIER and former chief economic adviser to the Government of India. Views are personal.

Disclaimer: These are personal views of the writer. They do not necessarily reflect the opinion of www.business-standard.com or the Business Standard newspaper

More From This Section

Don't miss the most important news and views of the day. Get them on our Telegram channel

First Published: May 11 2016 | 9:50 PM IST