40 Years Ago...and now: Non-farm growth greatly aided poverty reduction

)

Public discourse on inequality in India tends to centre on the estimate based on the National Sample Survey Organisation (NSSO)'s consumption expenditure data. But analysts argue this understates the true extent of inequality on two counts: First, inequality based on consumption expenditure tends to be less than that based on income data and second, as the NSSO data under-represent the rich, it leads to lower estimates of inequality.

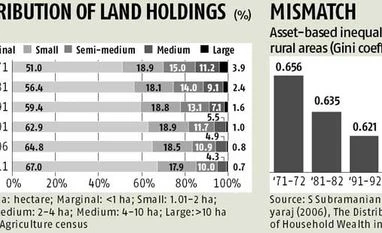

Some analysts say inequality estimates based on assets, especially land, show much higher levels of inequality in India. In 2004-05, consumption inequality (measured by the Gini coefficient) was 0.31, while those for assets (2002) and land (2003) were 0.62 and 0.76, respectively. Data on the distribution of holdings show 85 per cent of land holdings are small and marginal; only 0.7 per cent is classified as large.

Though it is argued the distribution of land has an impact on poverty reduction in rural areas, there are signs the relationship might be weakening. Various studies have shown now, the level of education is the primary determinant of income, indicating faster growth of the non-farm sector has greatly impacted poverty reduction.

However, this is not to be construed as a sign that the ownership of land doesn't matter. The ability of poor households to move out of poverty depends on their investment in physical and human capital. Land serves as collateral, on the basis of which poor households can access credit. Studies have shown the value of land does have a positive impact on access to credit.

Some analysts say inequality estimates based on assets, especially land, show much higher levels of inequality in India. In 2004-05, consumption inequality (measured by the Gini coefficient) was 0.31, while those for assets (2002) and land (2003) were 0.62 and 0.76, respectively. Data on the distribution of holdings show 85 per cent of land holdings are small and marginal; only 0.7 per cent is classified as large.

Though it is argued the distribution of land has an impact on poverty reduction in rural areas, there are signs the relationship might be weakening. Various studies have shown now, the level of education is the primary determinant of income, indicating faster growth of the non-farm sector has greatly impacted poverty reduction.

However, this is not to be construed as a sign that the ownership of land doesn't matter. The ability of poor households to move out of poverty depends on their investment in physical and human capital. Land serves as collateral, on the basis of which poor households can access credit. Studies have shown the value of land does have a positive impact on access to credit.

More From This Section

Don't miss the most important news and views of the day. Get them on our Telegram channel

First Published: Sep 23 2014 | 12:35 AM IST