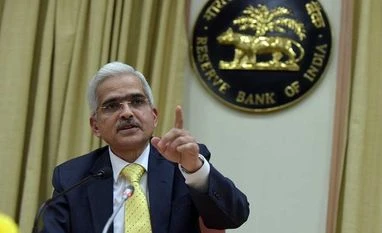

The fact is that the RBI, via the monetary policy committee, which has an equal number of nominees from the Union government, is required to maintain retail inflation, as measured by year-on-year changes in consumer price index, at the 4 per cent mark. However, the RBI has been given a leeway of 2 percentage points on either side of this central mark. This essentially means that there is enough possibility within the 4 percentage point band — between 2 per cent and 6 per cent retail inflation — for the RBI to focus on other concerns such as growth. It is possible to argue now that India has reasonably low inflation. After all, as the RBI Governor noted, India has witnessed significant disinflation since 2012-13, with headline CPI inflation moderating from an annual average of 10 per cent in 2012-13 to 3.7 per cent in 2018-19 so far (April-December).

Indeed, headline inflation was just 2.2 per cent in December 2018. Yet, while lower inflation should allow the RBI to focus more on growth, the fact is that India still has some worries on the inflation front. For instance, non-food, non-fuel inflation has been high (close to 6 per cent) and persistent. There are also concerns about financial stability, especially at a time when there is much churn in the non-banking financial sector. As such, it would be best that the RBI stays vigilant and does not let its guard down on its primary responsibility.

In fact, in the context of overall macroeconomic stability of the system, there are growing concerns on the fiscal policy front as well. Thanks to a flurry of policy choices — such as blanket farm loan waivers, higher minimum support prices, etc — it looks increasingly tough for governments, both at the Centre and the states, to meet their fiscal deficit targets. Indeed, with slippages on the revenue front as well as likely sops in the Budget, such as direct income support, it is quite likely that India will struggle to meet its public debt-to-GDP ratio target of 60 per cent. The trouble is, once put in place, it is politically difficult to overturn these policy choices, thus lending permanence to these expenditures. The RBI as well as the central government should not allow their “multiple responsibilities” to come in the way of their legally mandated commitment on inflation and fiscal deficit target, respectively.

)