Pranjul Bhandari: India's inflation divide

Urban India benefits from lower global prices while rural India, partly because of its structural ailments, is unable to do so with equal vigour

)

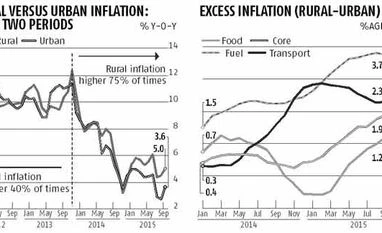

Inflation has fallen strikingly over the last several months, but the gains are not equally distributed. Rural inflation is running higher than urban inflation and its underlying trend is in fact above the Reserve Bank of India's upcoming January target. This "excess rural inflation" is apparent for fuel, transport, core and food (see charts 1 and 2). Digging deeper, we find that structural bottlenecks are not allowing rural Indians to benefit fully from global disinflation. Here are some key reasons why.

The dramatic fall of oil has pulled down both 'fuel' and 'transportation' prices. However, the pass-through has been lower for rural India. Data suggests that rural India's fuel mix is more geared towards domestically produced firewood, chips and biogas inputs, which are not a part of the global deflation cycle. On the other hand, fuel products more widely used in urban India, i.e. LPG and diesel, have benefitted from lower global prices.

On the transportation front, the benefits of lower diesel prices have been partly offset by stubbornly rising fares across bus, taxi, auto and motorcycles. Put differently, structural bottlenecks (e.g. insufficient transport networks, limited providers and insufficient competition) are getting in the way of rural India reaping the full benefits of cyclical developments (falling oil prices).

Ironically in the case of food, while most of India's food is produced in rural India, rural Indians seem to endure higher food price pressures. Overall food inflation in India has remained tepid, thanks partly to low global food prices making it possible to import food products that are in short supply. However, rural Indians do not seem to have benefitted as much from food imports as their urban counterparts. Insufficient distribution channels may be getting in the way of imported vegetables and oilseeds reaching rural areas, making these products more inflationary than they are at urban centres.

And most surprising of all, core inflation (calculated by removing food, transport and fuel from overall inflation) is running higher in rural areas than urban. Now, since core is influenced by growth, you might think rural growth is actually pretty strong. But that would be too hasty a conclusion.

True, core inflation is influenced by growth dynamics, but not by growth rates alone. Core inflation is actually determined by what economists call the output gap, i.e. the slack in the economy, calculated as the difference between actual and potential (or trend) growth. So, even if actual growth is low, but the potential has also fallen, the output gap may not be so wide after all, and that could keep core prices from falling rapidly. But we need to test this first.

Unfortunately, GDP data disaggregated neatly between rural and urban is not available. But what we do have are other proxy indicators (passenger car sales, commercial vehicle sales, consumer durables production and industry GDP for urban growth; and two-wheeler sales, tractor sales, consumer non-durable production and agriculture GDP for rural growth). And indeed, on calculating the output gap for each of our eight proxy indicators, we find a consistent message. It is smaller for rural India than for urban. And furthermore, we find that potential growth has fallen more in rural India than urban.

So what does all of this mean? Rural India has some structural disadvantages vis-a-vis urban India - structural bottlenecks are harsher, transport networks sparser and distribution channels insufficient. And this relative disadvantage is showing up more so now, as urban India benefits from lower global prices while rural India, partly because of its structural ailments, is unable to do so with equal vigour.

These structural bottlenecks, together with successive droughts, are also bringing down potential growth, keeping rural inflation closer to flaring up. If climate change makes monsoon patterns increasingly volatile, potential growth could become even more vulnerable.

All of these point to one solution. Higher investment in rural infrastructure and meaningful reforms in rural India's main occupation, agriculture, are needed to make growth weather-proof and put it on a higher and more sustainable path. And that could also go a long way in helping the RBI achieve and, more importantly, sustain its ambitious inflation targets.

The writer is chief India economist, HSBC

Disclaimer: These are personal views of the writer. They do not necessarily reflect the opinion of www.business-standard.com or the Business Standard newspaper

More From This Section

Don't miss the most important news and views of the day. Get them on our Telegram channel

First Published: Oct 24 2015 | 9:50 PM IST